An Evaluation of Swedish Monetary Policy between 1995 and 2005

Francesco Giavazzi and Frederic S. Mishkin

ISSN

ISBN

ISBN

Riksdagstryckeriet, Stockholm, 2006

2006/07:RFR1

Foreword

The Riksbank (Swedish central bank) has had an independent status in relation to the Riksdag and the Government since January 1999. This independent status is set out in Swedish law. Decisions regarding changes in interest rates are taken by an Executive Board consisting of six members who, according to the Riksbank Act (1988:1385), may not seek or take instructions on matters relating to monetary policy. According to the Instrument of Government, no public authority can determine how the Riksbank decides in matters relating to monetary policy.

The main task of the Riksbank is to maintain price stability. It should also promote a safe and efficient system of payments. According to the preparatory materials to the Riksbank Act, the Riksbank’s monetary policy should first and foremost strive to achieve a low and stable rate of inflation. In addition, the Riksbank should, without neglecting the objective of price stability, support the aims of general economic policy with the purpose of attaining sustainable economic growth and high levels of employment. Since 1 January 1995 the Riksbank has formally based Sweden’s operative monetary policy on an inflation target. The aim is that inflation, defined in terms of the consumer price index, is to be limited to 2 % per year, with a tolerance interval of

± 1 percentage unit.

As part of the parliamentary Committee on Finance’s

•Are the Riksbank’s overall objectives correctly formulated?

•Is the inflation target correctly formulated?

•Has the monetary policy pursued by the Riksbank achieved the inflation target during the period

•What methods of forecasting and analysis does the Riksbank use, and how is the Riksbank’s

•Is the Riksbank’s external communication effective and expedient?

•Does the Riksbank have the right instruments to achieve the inflation target?

•How does Sweden fare in comparison with other countries with inflation targets?

3

2006/07:RFR1 FOREWORD

In November 2005 the Committee on Finance decided to assign the evaluation jointly to Professor Frederic Mishkin at Columbia University and Professor Francesco Giavazzi at Bocconi University. They started their evaluation in January 2006. During the spring of 2006, Mishkin and Giavazzi visited Sweden on several occasions in order to collect information and discuss Swedish monetary policy with various stakeholders in Swedish society. Among others, they met representatives of the Riksbank, the social partners, academic life, the financial market, the Government and the Riksdag. Be- tween April and June 2006, the public also had the opportunity to submit their views on Sweden’s monetary policy to the evaluators, via the Riksdag website. In addition, some 20 referral bodies were invited to submit statements on Sweden’s monetary policy directly to the evaluators.

Mishkin’s and Giavazzi’s findings from their survey of Swedish monetary policy in the past ten years are presented in this Report from the Riksdag. The Committee has high hopes that the evaluation will further stimulate the important and already lively debate on Swedish monetary policy. The authors take full responsibility for the contents of the report.

Stockholm 28 November 2006

| Stefan Attefall | Pär Nuder |

| Chair of the | Deputy Chair of the |

| Committee on Finance | Committee on Finance |

4

2006/07:RFR1

Table of Contents

| Foreword.......................................................................................................... | 3 | |||

| 1 | Introduction................................................................................................ | 7 | ||

| 2 The Science of Monetary Policy................................................................. | 10 | |||

| 2.1 | The importance of price stability and a nominal anchor to | |||

| successful monetary policy ............................................................... | 10 | |||

| 2.2 | Fiscal and Financial Preconditions for achieving price stability........... | 14 | ||

| 2.3 | Central Bank Independence as an Additional Precondition .............. | 16 | ||

| 2.4 | Central Bank Accountability............................................................. | 19 | ||

| 2.5 | The rationale for inflation targeting .................................................. | 21 | ||

| 2.6 | The Flexibility of Inflation Targeting ............................................... | 26 | ||

| 2.7 | Central bank transparency and communication ................................ | 27 | ||

| 2.8 | The Optimal Inflation Target ............................................................ | 38 | ||

| 2.9 | The role of asset prices in monetary policy....................................... | 44 | ||

| 3 How Well Has Swedish Monetary Policy Been Run?.............................. | 48 | |||

| 3.1 | Taking stock of a decade: monetary policy and overall | |||

| economic performance ...................................................................... | 48 | |||

| 3.2 | Were interest rates set appropriately? ............................................... | 50 | ||

| 3.3 | The apparent puzzle of the |

55 | ||

| 4 An Evaluation of the Swedish Inflation Targeting Regime...................... | 56 | |||

| 4.1 | Is the Institutional Framework of the Inflation Regime | |||

| Appropriate ....................................................................................... | 56 | |||

| 4.2 | Is the technical expertise of the Riksbank of sufficiently high | |||

| quality?.............................................................................................. | 61 | |||

| 4.3 | Is the level and formulation of the inflation target appropriate? ....... | 65 | ||

| 4.4 | Is the Swedish Inflation Targeting Regime Sufficiently | |||

| Flexible?............................................................................................ | 66 | |||

| 4.5 | Does it Make Sense to Base Forecasts on Implicit Market | |||

| Interest Rates?................................................................................... | 68 | |||

| 4.6 | How Well is the Riksbank Communicating? .................................... | 69 | ||

| 4.7 | Is the Executive Board Set Up Properly?.......................................... | 73 | ||

| 5 | Conclusions and Recommendations......................................................... | 77 | ||

| 5.1 | The Conduct of Monetary Policy ...................................................... | 77 | ||

| 5.2 | Governance of Monetary Policy ....................................................... | 79 | ||

| Appendix 1: | Terms of reference for the evaluation .......................................... | 81 | ||

| Appendix 2: Schedule of the meetings we had with various parties....................... | 85 | |||

| Appendix 3: | List of the institutions which responded to our invitation | |||

| by sending written submissions................................................ | 89 | |||

| Appendix 4: | Figures .................................................................................................. | 90 | ||

| Endnotes....................................................................................................... | 109 | |||

5

2006/07:RFR1

1 Introduction

On November 10, 2005 the Riksdag Committee on Finance appointed Professor Francesco Giavazzi and Professor Frederic S. Mishkin to evaluate Swedish monetary policy between 1995 and 2005. The Committee expected the evaluation to follow the directives approved by the Committee on Finance on 31 May 2005 and which state (the complete text of the Guidelines appears in Appendix 1):

“The following issues shall be addressed:

•The Riksbank’s objective. The evaluator shall analyse whether there is any conflict of goals between the Riksbank Act’s price stability objective and the task of promoting stability in the financial system.

•The formulation of the inflation target. The evaluator shall analyse whether the inflation target is correctly formulated so as to ensure price stability. The evaluator shall analyse whether the inflation target also serves to support existing objectives of general economic development with the aim of achieving sustainable economic growth and high levels of employment. The evaluator shall highlight the consequences of the current system according to which the Riksbank independently formulates the operative objectives of monetary policy. The evaluator shall examine the target level, tolerance range, target variable and the clarifications that have been developed.

•Fulfilment of the inflation target and the shaping of monetary policy. The evaluator shall analyse to what extent current monetary policy has contributed to achieving the inflation target during the period

•Data and procedures for monetary policy decisions. The evaluator shall analyse the Riksbank’s forecasting and analysis methods, as well as the quality of the economic/statistical data on the basis of which decisions are made. The evaluator shall also highlight and analyse the Riksbank’s internal preparation and

•The Riksbank’s external communication. The evaluator shall analyse the Riksbank’s external communication with regard to the inflation target, current economic developments, changes in interest rates and the reasons for any deviations from the inflation target. The evaluator shall examine whether the Riksbank’s presentation of its decisions and the data on which its decisions are based (inflation reports, press releases, minutes, speeches, working reports) are such that monetary policy can be predicted and evaluated.

7

2006/07:RFR1 1 INTRODUCTION

•The instruments of monetary policy. The evaluator shall analyse whether the instruments of monetary policy that the Riksbank has at its disposal are sufficient for the Riksbank to achieve its goals.

•Comparison with other countries with inflation targets. The evaluator shall compare the shaping and results of monetary policy in Sweden with a few other countries with inflation targets.”

The following describes how we worked:

We started working on this evaluation in January 2006. For the first couple of months we studied documents that had been made available to us by the Se- cretariat of the Riksdag Committee on Finance and by the Riksbank, as well as similar evaluations that had been conducted concerning other central banks, and material we collected directly.

•We made the following visits to Stockholm:

•Professor Mishkin in the week of March

•Professor Giavazzi in the week of April

•Together in the week of May

•Professor Giavazzi was also at the Riksbank for a conference on “Central Bank Governance” on August

During these trips we met a variety of interested parties, in the Riksbank, in financial institutions, in labour unions, in the universities, in the ministry of Finance and in other Swedish organizations: a list of the people we met is in Appendix 2. We also had meetings with members of the Committee on Fi- nance of the Riksdag, of political parties represented in the Riksdag, and of the General Council of the Riksbank. On May 9 we met for two hours with the Swedish Prime Minister, Mr. Goran Persson.

We invited the public to submit their views in two ways, unsolicited and solicited:

•We advertised our evaluation on the website of the Riksdag (with an additional link on the Riksbank website). Through this channel we received some 50

•We sent approximately 20 letters to various Swedish organizations inviting more extended submissions. Through this channel we received 6 submissions. A list of the organizations which sent submissions is in Appendix 3.

We jointly wrote a first draft of the report in Italy May, soon after returning from Stockholm. During June and July we made further progress collecting additional information from the Riksdag Committee on Finance and from the Riksbank, and read the various

8

1 INTRODUCTION 2006/07:RFR1

finalized the report during the month of August and completed it during the month of September, except for some facts that still needed to be checked. A final version was ready in early October when it was sent to the translators.

We would like to thank Par Elfvingsson at the Riksdag Committee on Fi- nance, and Mikael Apel at the Riksbank for their assistance in organizing this work. Johanna Stenkula von Rosen at the Riksbank helped us produce some of the Figures in the Report. Our research assistant at Columbia Business School, Emilia Simeonova, did an excellent work.

We thank the Riksbank staff for their openness and frankness.

9

2006/07:RFR1

2 The Science of Monetary Policy

There have been major advances in economic research on monetary policy over the last thirty years and what we have learned has helped countries improve their economic performance substantially in recent years. In the 1990s and 2000s, inflation has dropped sharply in most countries, while employment fluctuations have if anything decreased. This research can help us evaluate Swedish monetary policy on a scientific basis. Here we examine what economic science tell us about how monetary policy should be conducted in nine key areas: 1) the importance of price stability and a nominal anchor to successful monetary policy, 2) fiscal and financial preconditions for achieving price stability, 3) central bank independence as an additional precondition, 4) central bank accountability as a necessary complement of independence, 5) the rationale for inflation targeting, 6) flexibility of inflation targeting, 7) central bank transparency and communications, 8) the optimal inflation target and 9) the role of asset prices in monetary policy.

2.1The importance of price stability and a nominal anchor to successful monetary policy

The realization that price stability and a nominal anchor are important to the successful conduct of monetary policy has stemmed from three intellectual developments in economics: 1) the recognition that expansionary monetary policy cannot raise output and employment except in the short run, 2) the realization that inflation is costly, and 3) the

2.1.1Expansionary monetary policy cannot raise output and employment except in the short run

Up until the 1970s, many economists thought that there was a

Attempts to lower unemployment below the natural rate would then only result in higher inflation. The

10

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

Neil Wallace made it clear that the public and the markets’ expectations about monetary policy have important effects on almost every sector of the economy.2 This research demonstrated that not only is there no

2.1.2 The high cost of inflation

Over the past three decades, economists and policymakers have become increasingly aware of the economic and social costs of inflation. The high inflation environment of the 1970s and 80s made the costs of inflation more apparent and led to a growing consensus that price stability – a low and stable inflation rate – provides substantial benefits to the economy. Price stability prevents overinvestment in the financial sector: in a high inflation environment the financial sector expands to profitably act as a middleman to help individuals and businesses escape some of the costs of inflation. Price stability lowers the uncertainty about relative prices and the future price level, making it easier for firms and individuals to make appropriate decisions, thereby increasing economic efficiency. Price stability also lowers the distortions that arise from the interaction of the tax system and inflation. Finally, price stability reduces strains on a country’s social fabric because it lessens conflict between different groups in the society each trying to make sure that its income keeps up with the rising level of prices at the expense of others. Inflation also increases poverty because it hurts the poorest members of society most: differently from the rich, the poor do not have access to financial instruments which would enable them to protect themselves against inflation

All of these benefits of price stability suggest that low and stable inflation can increase the level of resources productively employed in the economy, and can even help increase the rate of economic growth. Over time, the consensus has grown that inflation is detrimental to economic growth, particularly when inflation is at high levels.

2.1.3 The

Another important development in the science of monetary policy which emanated from the rational expectations revolution was the discovery of the importance of the

11

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

and we renege on the plan because doing so has

Monetary policymakers also face the

A central bank will have better inflation performance in the long run if it understands (and makes clear to the public) that it should not have an objective of raising output or employment above what is consistent with stable inflation and will not try to surprise people with an unexpected discretionary, expansionary policy. Instead, it should commit to keeping inflation under control.

However, even if a central bank recognizes that discretionary policy will lead to a poor outcome – high inflation with no gains in output – and so renounces it, the

2.1.4Price stability should be the overriding,

The inability of monetary policy to boost employment (except in the very short run), the high costs of inflation and the

A goal of price stability immediately follows from the benefits of low and stable inflation which promote a higher level of economic output. Furthermore, an institutional commitment to price stability is one way to make

12

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

the

But does accepting a price stability goal mean that the central bank should ignore concerns about output and employment fluctuations? Clearly, monetary policy should be directed at lowering both inflation and output/employment fluctuations around their optimal/natural levels. Indeed, defining the objectives of monetary policy in this way is standard in the academic literature. (Note that because output and employment usually move together, we use the terms output and employment interchangeably. However, there are cases in which output and employment do not move together, especially when there are productivity shocks as have recently occurred in Sweden where positive productivity shocks have resulted in high output growth while employment has been stagnant.)

The additional objective of lowering employment fluctuations explains why central banks should not try to attain price stability in the

In some countries, the United States for example, legislation asks the central bank to achieve two objectives: price stability and maximum employment

–and is thus known as dual mandate. Other countries, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the Euro area, for example, have a hierarchical mandate, in which the goal of price stability is placed first, but then say that as long as price stability is achieved, other goals such as high employment can be pursued.

The distinction between a dual and a hierarchical mandate is however largely academic. As long as price stability is a

Taken at face value, a dual mandate could be dangerous: if a dual mandate leads a central bank to pursue

13

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

mandate might lead to overly expansionary policy is a key reason why many countries have favored hierarchical mandates in which the pursuit of price stability takes precedence. Hierarchical mandates can also be a problem if they lead to the central bank focusing solely on inflation control, even in the

Article 2 of the Sveriges Riksbank Act states: “The objective of the Riksbank’s operations shall be to maintain price stability. The Riksbank shall also promote a safe and efficient payment system.” There is no explicit reference to a dual mandate in the Act itself. However, in the Bill (1997/98:40) where the Act was proposed the Government states that (section 7.3): “The objective of monetary policy shall be to maintain price stability. As an agency under Parliament, the Riksbank shall additionally without setting aside the objective of price stability, support the objectives for general economic policy with the intention of achieving sustainable growth and high employment.”

Thus the Riksbank de facto operates under a hierarchical mandate similar to those that have been written for the Bank of England and the European Central Bank.

2.1.5 A

Although an institutional commitment to price stability helps solve timeinconsistency and fiscal policy problems, it does not go far enough because price stability is not a clearly defined concept. Typical definitions of price stability are often of the type, you know it when you see it. Constraints on fiscal policy and discretionary monetary policy to avoid inflation might thus end up being quite weak because not everyone will agree on what price stability means in practice, providing both monetary policymakers and politicians a loophole to avoid making tough decisions to keep inflation under control. A solution to this problem is to adopt a nominal anchor that ties down exactly what the commitment to price stability means.

A nominal anchor is like a behavior rule which can help to prevent the

2.2Fiscal and Financial Preconditions for achieving price stability

Monetary policy is not done in a vacuum. There are two basic preconditions for monetary policy to be able to promote price stability and for adopting a credible nominal anchor: 1) responsible fiscal policy, 2) financial policies that

14

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

promote the safety and soundness of the financial system. We shall see that if a government has unsound fiscal and financial policies, monetary policy will be unable to keep inflation under control and this is why responsible fiscal policies and sound financial policies are preconditions for successful monetary policy. Happily, as we will see, Sweden currently meets these two preconditions. Nevertheless, we discuss them here because Sweden has not always met these preconditions in the past and they must never be taken for granted: without them monetary policy, no matter how well conducted, will eventually fail.

2.2.1 Responsible fiscal policy

Because the government has to pay its bills, just as we, private individuals, do, it has a budget constraint. When we spend more than we earn, we have to finance the excess spending by borrowing. If we cannot borrow, then our only option is to cut back our spending. When a government spends more than its revenues, that is, when it runs a budget deficit, it can similarly finance the deficit by borrowing, that is by issuing government debt. Unlike us, however, if the government cannot borrow, it has another option to finance a deficit: it can print money and use it to pay for its excess spending. When budget deficits get large, a government may not be able to borrow sufficient funds to cover the deficit. It may then resort to printing money directly or pressure the central bank to purchase government bonds (called monetizing the debt) which results in the same thing, an expansion of the money supply. The result is that when budget deficits get too large, pressure can arise that leads to expansionary monetary policy and high inflation will occur, making it difficult for the monetary authorities to be able to pursue price stability. In Sweden, there is less likelihood that expansionary fiscal policy can lead to expansionary monetary policy because the Maastricht Treaty, which Sweden has adopted, rules out printing money to finance budget deficits, and even during the Swedish banking crisis of the early 1990s, deliberate decisions were made not to finance the cost of the government bailouts of the banking system by monetizing the debt: the government had to issue bonds to pay for these bailouts. Nonetheless, even in an environment like Sweden’s, responsible fiscal policy promotes confidence that the central bank will never be put in a position where it has to expand the money supply to help the government finance its deficits.

2.2.2Sound financial policies that promote the safety and soundness of the financial system

Similarly, poor regulation and supervision of the financial system can result in large losses in bank balance sheets that make it impossible for the monetary authorities to raise interest rates to control inflation because doing so might lead to further losses and thus to a collapse of the financial system.

15

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

Also, significant losses in banks’ balance sheets can lead to large payments by the government to get the banks back on a sound footing, as indeed occurred in Sweden in the early 1990s, and this will lead to larger budget deficits. Larger deficits, as we have seen, can then also lead to an expansion of the money supply which produces high inflation. Sound financial policies are thus also essential for the attainment of price stability.

2.3Central Bank Independence as an Additional Precondition

Achieving price stability through the adoption of a credible nominal anchor, however, requires another precondition: in setting its policy instruments the central bank should be independent. There is always some discomfort in democratic societies in giving to

2.3.1 Goal Independence

Although there is a strong rationale for the price stability goal and for the adoption of a nominal anchor, who should set the goals for monetary policy? Should the central bank independently announce its commitment to the goal of price stability and what nominal anchor it chooses, or would it be better to have this commitment be mandated by the government?

Here the distinction between goal independence and instrument independence is useful. Goal independence is the ability of the central bank to set its own goals for monetary policy – say the goal of an inflation rate of 2% two years in the future. Instrument independence is the ability of the central bank to independently set the instruments of monetary policy, e.g. the level of the interest rate, to achieve its goals.

The principle, so basic to democracy, that the public must be able to exercise control over government actions strongly suggests that the goals of monetary policy should be set by the elected government. In other words, a central bank should not be goal independent. The corollary of this view is that the institutional commitment to price stability should come from the government in the form of an explicit, legislated mandate for the central bank to pursue price stability as its overriding,

Not only is a legislated mandate and goal dependence of the central bank consistent with basic principles of democracy, but it has the further advantage that it makes

16

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

ity mandate, it becomes harder for them to put pressure on the central bank to pursue

The reasoning above suggests that the central bank should be goal dependent in a parliamentary system as in Sweden: in other words the government should set the

Although there is a stronger case for the government setting the goal for monetary policy in the

If inflation is currently far from the

17

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

hand, there is an argument for the government having a role in setting the

Whether the central bank or the government should set

2.3.2 Instrument independence

Although the arguments above suggest that central banks should be goal dependent, there is a strong case that central banks should be instrument independent, that is should be allowed to set the policy interest rate that they deem appropriate to pursue the long run goal of price stability without interference from the government. We have seen that the

The fact that monetary policy needs to be forward looking in order to take account of the long lags in the effects of changes in interest rates on inflation provides another reason for instrument independence. Instrument independence insulates the central bank from the myopia that is frequently a feature of the political process arising from politicians' concerns about getting elected in the near future. Instrument independence thus makes it more likely that the central bank will be forward looking and adequately allow for the long lags from monetary policy actions to inflation in setting their policy instruments.

Recent evidence seems to support the conjecture that macroeconomic performance is improved when central banks are more independent. When central banks in industrialized countries are ranked from least legally independent to most legally independent the inflation performance is found to be the best for countries with the most independent central banks. 6

Both economic theory and the better outcomes for countries that have more independent central banks has lead to a remarkable trend toward increasing central bank independence throughout the world. Before the 1990s very few central banks were highly independent, most notably the Bundesbank, the Swiss National Bank and to a somewhat lesser extent the Federal Reserve. Now almost all central banks in industrialized countries and many in emerging market countries have a level of independence on par with the pre- 2000 Bundesbank and the Swiss National Bank. In the 1990s, greater independence was granted to central banks in such diverse countries as the New

18

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

Zealand, the United Kingdom, South Korea and those in the Euro area, as well as in Sweden.

2.4 Central Bank Accountability

A basic principle of democracy is that the public should have the right to control the actions of the government. The public in a democracy must have the capability to punish incompetent policymakers in order to control their actions. If policymakers cannot be removed from office or sanctioned in some other way, this basic principle of democracy is violated. In a democracy, government officials need to be held accountable to the public.

A second reason why accountability of policymakers is important is that it helps to promote efficiency in government. Making policymakers subject to sanctions makes it more likely that incompetent policymakers will be replaced by competent policymakers and creates better incentives for policymakers to do their jobs well. Knowing that they are held accountable for poor performance, policymakers will strive to get policy right. If policymakers are able to avoid accountability, then their incentives to do a good job drop appreciably, making poor policy outcomes more likely.

2.4.1Where should the political debate about monetary policy take place?

The need for central bank accountability suggests that monetary policy should be subjected to active public debate. But where should this debate take place? Should it take place in a country’s legislative branch, its parliament or congress? Should the executive branch, that is, government ministers, get actively involved in the monetary policy debate?

Before answering these questions we shall make two observations. First is the importance of a free and competent press where informed debates about monetary policy can take place. This requires high quality professional journalists, but also the active participation of a country’s best and better known economists. Such discussions are important because they can help increase the accountability of the central bank with the public.

Second, in discussing the role of public debates about monetary policy, one should never forget that if the credibility of the central bank to pursue price stability is weakened, inflation expectations will rise, leading to increased inflationary pressure as a result of demands by workers and businesses to raise their wages and prices. In that case, the central bank may be confronted with a difficult situation: if it does nothing, the nominal anchor will be weakened and inflation will rise; if it tightens monetary policy to restore the nominal anchor’s credibility, it may end up tightening too much and cause damage to the economy. A situation like this is exactly what the Riksbank confronted in the early years of its inflation targeting regime from

19

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

1993 to 1996, as we shall discuss in Section 3.2.1. As we shall see, the Riksbank’s concerns that inflation expectations were too high at that time led to a tightening of monetary policy, which ended up being too much, leading to an economic contraction and a decline of inflation below the Riksbank’s stated target. A loss of central bank credibility can thus lead to worse performance of monetary policy.

The analysis of the effects of a loss of central bank credibility indicates that there can be a cost from politicians’ criticisms of the central bank’s conduct of monetary policy. Political debate that takes the form of only criticizing policy actions, particularly when the central bank raises interest rates, but does not criticize the central bank for lowering rates when it might produce too much inflation, can be counterproductive because it will weaken the nominal anchor and produce worse economic outcomes. Political debate which focuses on whether a central bank is taking or has taken the appropriate measures to achieve price stability is, in contrast, likely to strengthen the nominal anchor.

Although there can be costs from political debate about the central bank, there are also major benefits. Political debate is central to the workings of a democracy and the central bank should not be excluded from this debate. Criticisms of the central bank both by politicians and participants in the markets are what make a central bank accountable and give the central bank the incentives to do its job well. Open monitoring and debate about the central bank also can enhance the central bank’s ability to learn from its mistakes. Whatever the form of the political debate, the gains from having political accountability for a central bank indicate that active political debate about monetary policy is vital.

The above reasoning argues strongly for having active political debate and scrutiny of monetary policy in a country’s legislative branch. It also suggests that debate about the performance of the central bank, particularly after outcomes are known, has great value in enhancing central bank accountability.

Debate and criticism of the central bank from the executive branch or government ministers is far more problematic, however, particularly if it is meant to influence the central bank’s current decisions. Because government ministers have greater influence over legislation that affects the powers and resources of the central bank, government ministers, particularly the prime minister or minister of finance, have substantial power to punish or reward the central bank. When a government minister criticizes central bank actions, and in particular criticizes the central bank when it raises interest rates, central bank credibility is likely to be weakened. The result could actually be the opposite of what the government minister wants, because in order to restore credibility to the nominal anchor and keep inflation expectations from rising, the central bank is even more likely to raise interest rates further, which could lead to a contraction in economic output and employment.

Recognition of the danger of having government ministers criticize monetary policy has led some governments to renounce criticizing central bank

20

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

decisions, with positive outcomes. The recent relationship between the executive branch and the Federal Reserve in the United States is quite illustrative of the benefits of not having the political debate about monetary policy occur through comments by government officials. Early in Bill Clinton’s first presidential term, Robert Rubin, who later became the U.S. Treasury Secretary, but who worked in the White House heading the National Economic Council, convinced President Clinton that it would be a mistake for the President (or Rubin himself for that matter) to criticize the Federal Reserve’s raising of interest rates in early 1994. Doing so would only lead to a weakening of the credibility of the Fed, an upward surge in inflation expectations, a resulting rise in

2.5 The rationale for inflation targeting

Economists and policymakers may have come to the conclusion that it makes sense to adopt a nominal anchor. But which anchor should be chosen? There are three basic types of nominal anchors for countries that have an independent monetary policy: monetary targets, inflation targets and implicit but not explicit nominal anchors. (An alternative nominal anchor is an exchange rate target (peg), which, with open capital markets, as in Sweden, implies that a country no longer has an independent monetary policy that can focus on domestic considerations. We discuss exchange rate targets in the context of the role of asset prices in monetary policy in a later section.) What are the relative merits of these alternative anchors?

2.5.1 Monetary targeting

Monetary targets were once the nominal anchor of choice, but a monetary target will have trouble serving as a strong nominal anchor when the relation-

21

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

ship between monetary aggregates and inflation is unstable. This relationship is likely to become even more unstable after a financial liberalization or technological innovations which make it more difficult to define what money actually is. Indeed, this is exactly what happened in the countries that adopted monetary targeting. Gerald Bouey, the governor of the Bank of Canada, colorfully described his central bank’s experience with monetary targeting by saying, “We didn’t abandon monetary aggregates; they abandoned us.”

Note that Germany (and to a lesser extent Switzerland) had substantial success with monetary targeting. Still, it is important to recognize that these successes often occurred (certainly up to the late 1980’s) in an environment characterized by rather strict financial regulation, where the relationship between monetary aggregates and inflation was relatively stable. Moreover, the Bundesbank and the Swiss National Bank were not bound by the monetarist orthodoxy advocated by Milton Friedman, who suggested that a monetary aggregate should the primary focus of monetary policy and that such an aggregate should be kept on a

2.5.2 Inflation targeting

The disappointments with monetary targeting led to a search for a better nominal anchor and resulted in the development of inflation targeting in the 1990s. Inflation targeting evolved from monetary targeting by adopting its most successful elements: an institutional commitment to price stability as the primary

Inflation targeting superseded monetary targeting for several reasons. First, inflation targeting does not rely on a stable

22

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

change will have on inflation and future output, while inflation targeting would not. Third, an inflation target is readily understood by the public because changes in prices are of immediate and direct concern, while monetary aggregates are farther removed from peoples’ experience. (What percentage of a population would know the difference between M0, M1, M2 or M3?) Inflation targets are therefore better at increasing transparency of monetary policy because they make the objectives of the monetary authorities clearer. Fourth, inflation targets increase central bank accountability because the performance of the central bank can now be measured against a clearly defined target. Monetary targets work less well in this regard because of the unstable

Because an explicit numerical inflation target increases the accountability of the central bank in its task of controlling inflation, inflation targeting also has the potential to reduce the likelihood that a central bank will suffer from the

2.5.3Monetary policy with an implicit but not explicit nominal anchor

A third approach to conducting monetary policy is the one used by the Federal Reserve under Alan Greenspan. The Greenspan Fed had a nominal anchor that was implicit but not explicit and involved an overriding concern by the Federal Reserve to control inflation in the

23

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

engaged in a preemptive strike against a weakening economy and deflation starting in January 2001, with the result that the recession in

There are several disadvantages of an implicit anchor based on the reputation of a single individual as in the United States. One disadvantage is its lack of transparency: it leads to constant guessing game about the central bank’s goals which creates unnecessary volatility in financial markets and arouses uncertainty among producers and the general public. This was illustrated not only by the repeated inflation scares in the 1990’s, but also by the sharp swings in

Furthermore, the opacity of a central bank without an explicit nominal anchor makes it hard to hold a central bank accountable to the public: its leadership can’t be held accountable if there are no predetermined criteria for judging its performance. Low accountability, as we already noted, may also make the central bank more susceptible to the

An additional problem with a central bank not having an explicit nominal anchor is that it – and particularly its leader – is more likely to find its credibility being challenged, leading to what Marvin Goodfriend has called an “inflation scare” – a spontaneous increase in inflation fears that is reflected in a sharp rise in

The most serious problem with the use of an implicit but not explicit nominal anchor is its strong dependence on the preferences, skills, and trustworthiness of the individuals in charge of the central bank. Under Alan Greenspan, the Fed has emphasized

24

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

Bernanke and who will also be strongly committed to inflation control. In the past, after a successful period of low inflation, the Federal Reserve has reverted to inflationary monetary policy – the 1970s are one example. Without an explicit nominal anchor like an inflation target, this could happen again.

Another disadvantage of using an implicit but not explicit nominal anchor is inconsistency with democratic principles. As we have seen, central bank independence is critical to producing low inflation outcomes, yet the practical economic arguments for central bank independence coexist uneasily with the presumption that government policies should be made democratically, rather than by an elite group. In contrast, use of an inflation target as a nominal anchor makes the institutional framework of monetary policy more consistent with democratic principles and avoids some of the above problems. Use of an inflation target involves delegation of policy with a specific mandate, rather than

2.5.4 Economic performance under inflation targeting

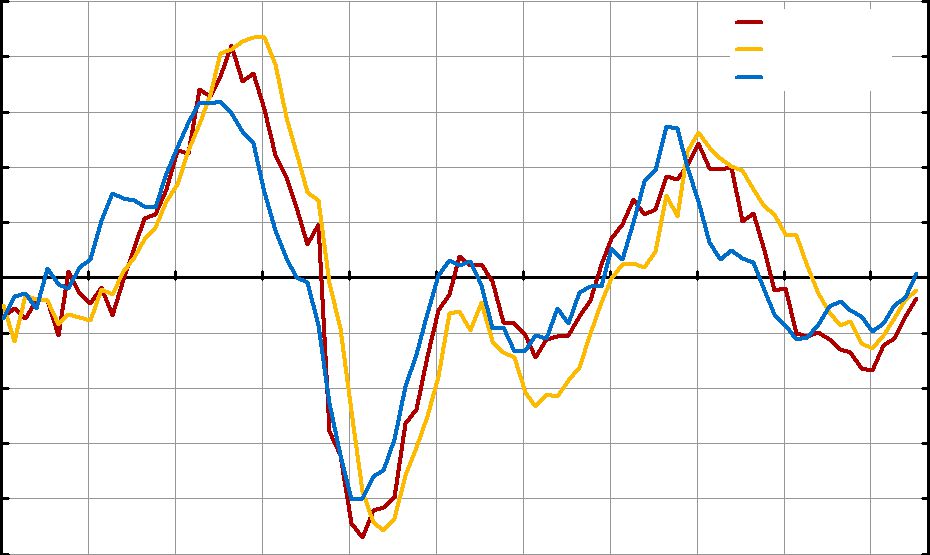

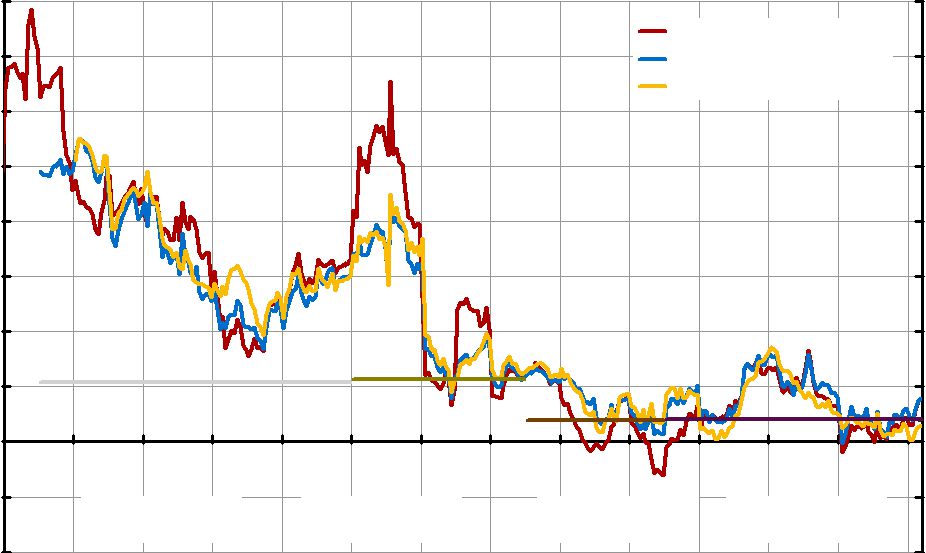

Given its advantages, it is not surprising that the performance of inflation targeting has been quite good in controlling inflation. Inflation targeting countries seem to have significantly reduced both the rate of inflation (Figure

1)and inflation expectations beyond what would likely have occurred in the absence of inflation targets. Furthermore, once down, inflation in these countries has stayed down and inflation volatility has declined (Figure 2): following disinflations, the inflation rate in targeting countries has not bounced back up during cyclical expansions of the economy as used to occur in the past.

One concern about inflation targeting is that a sole focus on inflation may lead to monetary policy that is too tight when inflation is above target and thus may lead to larger output and employment fluctuations. Indeed, the opposite is what happened (Figure 3). (However, a drop in output volatility has also occurred in many countries that have not adopted inflation targeting, and it is thus not absolutely clear that it is due to better performance of monetary policy. It could simply be the result of smaller shocks to the economy in recent years. This is currently a very active area of research). To see how inflation targeting could lead to lower, rather than higher, output volatility, we need to understand that there are two factors that are the key drivers of inflation: inflation expectations and the amount of slack in the economy, described by the

25

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

around the target: deviations of inflation from the target will therefore be highly correlated with the output gap. Thus stabilizing inflation also helps to stabilize output gaps, in other words it can help stabilize fluctuations of output around potential output.

To see how this would work, consider a negative demand shock, such as a sudden decline in consumer confidence which causes consumers to cut back on their spending which then leads to a decline in output relative to potential. The result is that inflation will fall below the inflation target in the future and the central bank will pursue an expansionary policy in order to prevent an undershooting of the target. The expansionary policy raises demand and output back up to potential, thus keeping inflation close to the target. Indeed, because an inflation target helps anchor expectations, the central bank will be willing to be more aggressive in pursuing expansionary policy because it does not have to worry that this expansionary policy will lead an inflation scare with a blow out of inflation expectations.

Summarizing: inflation targeting has not only produced good inflation outcomes, but has also been associated with declines in output fluctuations. The better performance on output fluctuations from inflation targeting regimes has surprised many initial skeptics, because an increased focus on controlling inflation, everything else equal, should lead to larger, not smaller output fluctuations. However, if inflation targeting produces a stronger nominal anchor, which is a key to successful economic performance, then inflation targeting can lead not only to a decline in inflation but also output volatility.

2.6 The Flexibility of Inflation Targeting

Although inflation targeting has many advantages, it has to be designed well to produce the best possible outcomes. What is best practice for inflation targeting regimes? First we look at what degree of flexibility needs to be built into the inflation targeting regime.

Price stability is a means to an end, a healthy economy, and should not be treated as an end in itself. Thus, central bankers should not be obsessed with inflation control, and become what Bank of England Governor, Mervyn King, has characterized as "inflation nutters". Clearly the public cares about output as well as inflation fluctuations, and so the objectives for a central bank in the context of a

Although, as we have seen, in the face of demand shocks, reducing inflation fluctuations also helps reduce fluctuations of output around potential output, for one type of shock too much focus on hitting an inflation target exactly could magnify output fluctuations. If the economy is hit by a negative shock to supply, say a large increase in energy prices, inflation can rise at the same time that output falls below potential (a negative output gap).9 In this

26

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

situation, if a central bank tightens to bring inflation immediately back to the target level, output would fall further and this could lead to increased output gap fluctuations. Because central banks should care about output gap fluctuations, the presence of supply shocks indicates that inflation targeting should not try to always bring inflation quickly down to the target. Rather, inflation targeting needs to be quite flexible and in the face of supply shocks should shoot for having inflation come back down to the inflation target only gradually. Lars Svensson has characterized this approach to conducting monetary policy as “flexible inflation targeting”.10 Indeed, his research and that of others, particularly Michael Woodford, shows that the horizon over which inflation should be brought back down to the

The reasoning above suggests that inflation targeting should not involve a sole focus on inflation or a simple rule that indicates that policy rates should be moved in a particular direction depending on the state of the economy or forecasts of inflation. Instead, an inflation targeting regime should display substantial concern about output fluctuations and thus pursue flexible inflation targeting with varying horizons for bringing inflation back to its target. Central bankers in inflation targeting countries do indeed express concerns about fluctuations in output and employment when discussing how they are conducting monetary policy and have been willing to minimize output declines by gradually lowering

Flexible inflation targeting should be seen as a way of pursuing an objective of minimizing inflation and output gap fluctuations, but with an emphasis on couching policy in terms of the path of inflation because, as we will see, measures of output gaps are notoriously unreliable.

2.7 Central bank transparency and communication

Inflation targeting regimes put great stress on making policy transparent and on regular communication with the public.

27

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

monetary policy strategy. While these techniques are also commonly used in countries that have not adopted inflation targeting,

The above channels of communication, especially the Inflation Reports, are used by central banks in

The higher transparency and improved communication of central banks who have adopted inflation targeting is one of the major strengths of this monetary policy framework. Not only does it help decrease uncertainty, with the benefits described earlier, but transparency also goes hand in hand with increased accountability.

2.7.1How should the central bank discuss its objectives for monetary policy?

As we have seen, central bank objectives should include both lowering inflation and employment/output fluctuations. However, many central banks are extremely reluctant to discuss concerns about output fluctuations even though their actions show that they do care about them. This lack of transparency is what one of the authors’ of this evaluation has called the “the dirty little secret of central banking”.

Some central bankers fear that if they are explicit about the need to minimize output fluctuations as well as inflation fluctuations, politicians will use this to pressure them to pursue a

28

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

However, the unwillingness of central banks to discuss their concerns about reducing output fluctuations creates two very serious problems. First, a

The case for central bank transparency with regard to its concerns about output fluctuations is quite strong. But how can central banks do this? One answer is that the central bank can make it absolutely clear that it takes output fluctuations into account when it targets inflation. This is exactly what the Norges Bank has done with the following statement that appears at the beginning of its Inflation Report: “Norges Bank operates a flexible inflation targeting regime, so that weight is given to both variability in inflation and variability in output and employment.” The Norges Bank thus makes it absolutely clear that its objectives include not only reducing inflation fluctuations but also output (employment) fluctuations and that flexible inflation targeting is a way of doing this.

The second way of making it clear that the central bank also has an objective of reducing output fluctuations is that the central bank can announce that it will not try to hit its inflation target over too short a horizon because this would result in unacceptably high output losses, especially when the economy gets hit by shocks that knock it substantially away from its

Monetary authorities can further the public's understanding that they care about reducing output fluctuations in the long run by emphasizing that monetary policy needs to be just as vigilant in preventing inflation from falling too low as it is from preventing it from being too high. They can do this (and some central banks have) by explaining that an explicit inflation target may help the monetary authorities stabilize the economy because it allows them to be more aggressive in easing monetary policy in the face of negative demand shocks to the economy without being concerned that this will cause a blowout

29

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

in inflation expectations. (However, in order to keep the communication strategy clear, the explanation of a monetary policy easing in the face of negative demand shocks needs to indicate that it is consistent with the preservation of price stability.)

In addition, central banks can also clarify that they care about reducing output fluctuations by explaining that when the economy is clearly below any reasonable measure of potential output – i.e., the output gap is sure to be negative – they will take expansionary actions to stimulate economic recovery. In this case, measurement errors in the estimate of potential output – a serious concern, as we discuss in the next paragraph – are likely to swamped by the size of the output gap, so there will be little doubt that expansionary policy is appropriate and that inflation is unlikely to rise from such action, so that the credibility of the central bank in its pursuit of price stability will not be threatened.

2.7.2Should central banks announce an output (employment) target?

Given that we have argued that central banks should make clear that they do have an objective of reducing output fluctuations, why shouldn’t they announce an output (or employment) target as well as an inflation target? After all, announcing an output or employment target seems like a natural way to express concerns about output or employment fluctuations. This obvious answer is not the right one, however, because potential output and the associated natural rate of employment (or unemployment) are so hard to measure. This is why, the section above advocates that central banks should express their concerns about output/employment fluctuations by describing how the targeted path of inflation is modified to help minimize these fluctuations. (We shall return to the difference between output and employment, that we already discussed in

One measurement problem for potential output occurs because the monetary policy authorities have to estimate it with

An even more severe measurement problem occurs because ‘conceptually’ economists are not even sure theoretically what potential output means. Some economists argue that conventionally measured potential GDP based on a trend, the most common method, differ substantially from more theoretically

30

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

grounded measures based on the output level that would prevail in the absence of nominal price stickiness.

The fact that it is so hard to measure potential output or even know theoretically how to define it, indicates that announcing an output or employment target would lead to worse policy outcomes. This is illustrated by the experience of the United States in the 1970s when the Federal Reserve had a hard time measuring potential output. Under Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns, the Fed put a lot of weight on hitting an output target. Unfortunately, the Fed had such inaccurate estimates of potential output that it thought that there was a lot of slack in the economy when there wasn’t. The result was that it did not tighten monetary policy sufficiently during that period even when inflation was rising to double digit levels, producing what has been referred to as the “Great Stagflation” in which inflation rose to very high levels and yet employment fluctuations continued to be very high. Research has shown that the reason for the Federal Reserve's poor performance during the 1970s was not that it was unconcerned with inflation, but rather that it focused too much on targeting output.

It is true that there are measurement problems with inflation as well as output gaps, but both the conceptual and

Announcing an employment target may be even more problematic than announcing an output target because unforeseen shocks to productivity can alter the relationship between the natural rates of output and employment. In many countries, not only in Sweden, we have seen unexpected increases in productivity in recent years so that very rapid output growth has not been accompanied by employment growth. Because predicting productivity shocks has been very difficult in recent years, forecasting the natural rate of unemployment may be even harder than forecasting the natural rate of output. For this reason, central banks are often even more reluctant to discuss employment targets than output targets.

Announcement of an output or employment target might also increase the tendency for politicians to pressure the central bank to pursue expansionary policies that could exacerbate the

31

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

2.7.3 Should central banks publish inflation forecasts?

Almost all

The publication of inflation forecasts might require several steps. First, the monetary policy committee (in the Swedish case the members of the Executive Board of the Riksbank) might have to learn how to agree on a forecast (and on the path of policy interest rates on which such a forecast is based, an issue to which we turn to later.) and the degree of uncertainty in such a forecast. Once it has accomplished this, it can then publish this information using a

There is one argument against a central bank publishing its forecasts which has been made by Stephen Morris and Hyun Song Shin.13 Market participants may have information that the central bank does not have, or have useful and different ways to interpret some of the same information. But if market participants put a high value on central bank forecasts, they may modify their own forecasts to bring them closer to those of the central bank. The result is that their forecasts would not reflect the full amount of information that they have. There is thus a possibility that the private sector will end up with less information about the economy and so their decisions will then be worse. The

32

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

better known by the central bank, and so there is still a very strong case for central banks to publish their forecasts.14

2.7.4On what interest rate path should the central bank condition its forecasts?

Given that publishing forecasts is highly beneficial, there is still the question of what path of the policy interest rate the forecast should be conditioned on. There are three choices: 1) a constant interest rate path, 2) market forecasts of the future policy rates, or 3) a central bank projection of the path for policy interest rates.

A constant interest path would almost surely never be optimal because future projected changes in interest rates will be necessary to keep inflation on the appropriate target path. The second choice is also problematic for several reasons. Using market forecasts for the interest rate path may give the impression that the central bank’s decisions are driven by the analysts in the financial sector. This may weaken confidence in the central bank’s capabilities for making independent decisions and could create concerns that the central bank is a captive to participants in the financial market. In addition, if the central bank just does what the market expects it to do there is a circularity when the central bank sets its policy rate on the basis of market forecasts because the markets forecasts are just guesses of what the central bank will be doing. In this case, there is nothing that pins down the system and inflation outcomes could be indeterminate. Of course, the central bank may not intend to follow the market’s expectations, but if this is the case, the central bank is clearly not being very transparent when it bases its forecasts of the economy on market expectations of its actions. An additional, but more minor, problem of conditioning on market forecasts of policy rates is that these forecasts require making assessments of the risk (term) premiums embedded in interest rates. There is not complete agreement on the best way to do this and this is currently an active area of economic research. Market participants may not be completely happy with the way the central bank chooses to extract market forecasts of the policy path from interest rates and this could create some doubts about the quality of the central bank forecasts.

Theory thus favors the third one, the central bank projection of the policy path used to build the inflation forecasts published by the bank. Clearly, an inflation forecast is meaningless without specifying what policy it is conditioned on, and this is why Lars Svensson has made a strong case for a central bank to publish its projection of the

Some central banks, including the ECB and Bank of England, base their inflation forecasts not on the interest path that they deem appropriate to de-

33

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

liver price stability, but rather on the path implicit in the market yield curve— the second approach discussed above. These central banks argue that whenever such a path implies an inflation forecast that deviates from the bank's target, the monetary policy committee will follow a different path. If this happens, transparency would require that the central bank reveal some information about its different view on the future path of policy rates: but when it does so its forecast would necessarily differ from what was previously published. Not surprisingly, this can create confusion in the public and in the financial markets.

Although the argument for announcing the projection of the policy path is theoretically sound, it does create some problems. One objection to a central bank announcing its policy projection, raised by Charles Goodhart, a former member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England, is that it would complicate the decision making process of the committee that makes monetary policy decisions. The current procedure of most central banks is to make decisions only about the current setting of the policy rate. Goodhart argues that “a great advantage of restricting the choice of what to do now, this month, is that it makes the decision relatively simple, even stark.”16 If a policy projection with

The second problem with announcing a projection of the policy rate path is that it might complicate communication with the public. Although economists understand that any policy path projected by the central bank is inherently conditional because changes in the state of the economy will require a change in the policy path, the public is far less likely to understand this distinction. Indeed, there is a danger that the public and the markets will come to expect that decisions about policy rates will have already been made before the next monetary policy committee meeting. When new information comes in and the central bank moves the

34

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

changes his position – even if this reflects changes in circumstances and thus reveals sound judgment – such a shift is vulnerable to attacks by his or her opponents that he or she does not have leadership qualities. Wouldn’t central banks be subject to the same criticism when changing circumstances would force them to change the

Summarizing, although there are strong arguments for a central bank to publish its projections of the policy path, the problems with doing so suggest that how this should best be done is very controversial. There are three possible choices: 1) the most likely (or the mean) policy path could just be published,18 2) the most likely policy path could be published along with shaded areas showing how much uncertainty there is about such a path, using a fan chart; and 3) a fan chart of the policy path could be published without the most likely path. Currently very few central banks publish their projections of the policy path. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand, however, uses the first procedure in which only the most likely policy path is published, while the Norges Bank uses the second procedure and publishes a fan chart which also includes the most likely policy path.

We have serious doubts about the first procedure, particularly for central banks in which the decision about setting policy rates is done by a committee rather than an individual. Decisions about setting policy rates at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand are made solely by the Governor, and so the complications with having a committee decide the policy projection are not present. Thus the fact that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has been able to publish only the most likely policy path does not tell us whether this would work well in other central banks which have committees decide on policy. Just publishing the most likely policy path also leaves the central bank vulnerable to criticisms that it is not doing what it said it would do when it deviates from the projected path.

The second procedure used by the Norges Bank has more to recommend it. It does indicate that the policy projection is highly uncertain. The fan chart will make it clear to market participants that when a central bank deviates from the most likely projection, this does not mean that it has flip flopped. Rather it makes it easier for the central bank to explain that the economy did not evolve quite as the central bank thought was most likely. The one problem with this procedure is that the public and the media may focus too much on the most likely path in the fan chart, and this could lead to some of the problems we have mentioned above.

We are most comfortable with the third procedure of just publishing the fan chart but not publishing the most likely path. The fan chart is consistent with full transparency of the central bank because it would show the direction the central bank expects for the policy path but would also indicate the degree of uncertainty the central bank has about the future evolution of the economy

35

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

and the policy path. Also publication of the fan chart (and of the data needed to construct it) would enable market participants to derive the most likely policy path, so this information would not be hidden. However, by not publishing the most likely policy path, the central bank could emphasize and make it much clearer to the public that it has not made a commitment to achieving the most likely policy path. and that the most likely policy path is not that special. Therefore, not publishing the most likely policy path is actually more transparent, as long as the data for construction of the fan chart is made publicly available.

An additional advantage of not publishing the most likely policy path is that members of the policy committee at the central bank who disagreed with the implied most likely path might be more comfortable about agreeing to the fan chart without the most likely path because they could state that their view of the most likely path is still well within the range of paths indicated by the fan chart. There is a precedent for publishing only fan charts without the most likely policy path: the Bank of England in its Inflation Report does not publish the most likely path of the variables for which it provides forecasts, but instead only publishes fan charts. Our suspicion is that the Bank of England does not publish the most likely paths of variables it forecasts because it wants to emphasize to the markets that its forecasts are uncertain. (The Bank of England, however, does not publish information on its projection of the policy path, but rather conditions its forecasts on the market forecasts of policy rates.)

2.7.5Should central banks announce their objective function for monetary policy?

In order for the public and the markets to fully understand what a central bank is doing they need to understand the central bank’s objectives. Because infla-

We think that there are problems with the suggestion that a central bank should announce its “objective function”. The first problem with announcing an objective function is that it might be quite hard for members of a monetary policy committee to specify an objective function. Members of monetary policy boards don’t think in terms of objective functions and would have a very hard time in describing what theirs is. Monetary policy committee members could be confronted with hypothetical choices about acceptable paths of inflation and output gaps and such choices would reveal how much they care about output versus inflation fluctuations. Although committee members would be able to do this when confronted with a real world situation, our

36

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

experience with seeing how policy boards work suggest that members would find this difficult to do when the choices are only hypothetical.

A second problem, raised by Charles Goodhart, is that it would be difficult for a committee to agree on its objective function. Not only individual committee members might have trouble defining their own objective function, but the composition of the committee changes frequently and the views of existing members may also change. Deciding on the committee’s objective function would thus substantially increase the complexity of the decision process and might also be quite contentious. As a result it could weaken the quality of monetary policy decisions by distracting the attention of committee members away from the analysis of developments in the economy.

A third problem is that it is far from clear who should decide on the objective function. If the members of the monetary policy board do so, isn’t this a violation of the democratic principle that the objectives of bureaucracies should be set by the political process? An alternative would be for the government to do so. But if we think that it would be hard enough for a monetary policy committee to do this, it would clearly be even more difficult for politicians to decide on the objective function.

Even if it were easy for the monetary policy committee or the government to come to a decision on the objective function, would it be easy to communicate it to the public? If economists and members of a monetary policy committee have trouble quantifying their objective function, is it likely that the public would understand what the central bank was talking about when it announced it objective function? Announcement of the objective function would be likely only to complicate the communication process with the public.

The announcement of the central bank’s objective function can add a further complication to the communication process that might have even more severe consequences for the ability of the central bank to do its job well. The beauty of inflation target regimes is that by focusing on one target – inflation

–communication is fairly straightforward. On the other hand, with the announcement of the objective function, the central bank may lead the public to believe that it will target on output as well as inflation. As we have already mentioned, discussion of output as well as inflation objectives can confuse the public and make it more likely that the public will see the mission of the central bank as elimination of

Given the objections raised here, it is not surprising that no central bank has revealed its objective function to the public.

2.7.6 Should central banks publish their minutes?

The benefits of transparency suggest that central banks should provide a substantial amount of information about how decisions about monetary policy are made. Central bank minutes, the summary of the deliberations about monetary policy by the members of the policy board, provide an important

37

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

vehicle for doing exactly that and there is thus a strong argument for them to be released in a timely manner. Most central banks do indeed publish minutes within a couple of weeks of their policy decisions, and the Riksbank is no exception.

However, could transparency be pushed even further by having the arguments expressed in policy board meetings attributed to the individual board members who make them? Our view is that the answer is no. A counterexample to pushing transparency further in this direction is provided by the experience of the Federal Reserve which publishes transcripts of its FOMC (the policy board) meetings five years after the meeting. (The publication of these transcripts is unique to the Fed and it occurred because Arthur Burns, the chairman of the Federal Reserve decided to install a taping system without the knowledge of his fellow board members. When this was publicly revealed during Alan Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chairman, the U.S. Congress insisted that the transcripts be published and the Fed did not feel it could resist the congressional request.) Participants in the FOMC who saw how the FOMC operated both before and after it was announced that the transcripts would be released have indicated that policy discussions became much more formal and less interactive once FOMC members became aware that their statements would be attributed to them. This experience suggests that attributing arguments to particular members would lead to less effective policy board meetings because it would reduce free discussion and make monetary policy committee meetings less lively.

Although we do not believe that the arguments of individual members in policy board meetings should be published because it would inhibit frank discussion, we do believe that individual board members should have some accountability for their actions: this suggests that their votes on policy decisions should be recorded as is done in Sweden and in the United Kingdom.

2.8 The Optimal Inflation Target

We have already seen that good economic performance requires that an inflation targeting regime be designed to be flexible. In addition, there are questions about how the target itself should be chosen to generate the best economic performance. There are three issues that must be dealt with in designing the optimal inflation target: 1) what price measure should be used in the inflation target?, 2) what is the optimal level of the inflation target? and in particular 3) should the target be in terms of price level or in terms of inflation?

2.8.1 What price measure should be used in the inflation target?

Economic theory shows that an inflation target that uses a measure of inflation which puts more weight on prices that move sluggishly (referred to as sticky prices) will do better at reducing employment and output fluctuations. 20

38

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1

If there is a high weight put on more flexible prices, monetary policy is likely to overreact to

One important element of the consumer price index (CPI) in many countries is mortgage interest payments which are calculated as the price of

In addition, since the mortgage rate in most countries is an interest rate that is not adjusted for inflation (a nominal rate rather than a real rate), a CPI that includes mortgage interest payments will overstate inflation when nominal rates are rising because expectations of inflation are rising. This can mean that when the central bank is raising interest rates to contain inflation, the inflation measure will be biased upward, which could induce even tighter monetary policy. The resulting over tightening would then lead to an unnecessary output decline.

Targeting on an inflation measure that includes mortgage interest payments is thus problematic and this is an important reason why inflation indices used to guide monetary policy in the United States, the United Kingdom and the Euro area exclude mortgage interest payments. Indeed, the view that the measure of inflation used for the target should put more weight on sticky prices suggests that monetary policy should target on a measure of core inflation that removes volatile prices, like food and energy, from the price index— although no specific core measure will always be appropriate because what are sticky price items change over time. This is why many central banks use “core inflation” measures to guide monetary policy.

2.8.2 What is the optimal level of the inflation target?

A key question for any central bank using an inflation targeting strategy is what the

39

2006/07:RFR1 2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY

criterion. Some economists, Martin Feldstein being a prominent example, have argued for a

One argument against setting the

The argument by

A more persuasive argument against an inflation goal of zero is that such a goal makes it more likely that the economy will experience episodes of deflation: with a mean of zero, half the time inflation would have to be negative (deflation). Deflation can be highly dangerous because debt contracts in industrialized countries frequently have long maturities, so that a deflation, even if anticipated in the

The dangers of deflation imply that undershooting a zero inflation target (i.e., a deflation) is potentially more costly than overshooting a zero target by

40

2 THE SCIENCE OF MONETARY POLICY 2006/07:RFR1