Trends in GDP Growth and its Driving Factors

Teodora Borota Milicevic

Bilaga 1 till Långtidsutredningen 2023

Stockholm 2023

SOU 2023:86

SOU och Ds finns på regeringen.se under Rättsliga dokument.

Svara på remiss – hur och varför

Statsrådsberedningen, SB PM 2021:1.

Information för dem som ska svara på remiss finns tillgänglig på regeringen.se/remisser.

Layout: Långtidsutredningen 2023, Regeringskansliet

Omslag: Elanders Sverige AB

Tryck och remisshantering: Elanders Sverige AB, Stockholm 2023

ISBN

ISBN

ISSN

Förord

Långtidsutredningen 2023 har utarbetats av ett fristående projektgrupp inom Finansdepartementets enhet för ekonomisk politik och fördelning. Inom ramen för utredningen har ett antal specialstudier tagits fram, vilka publiceras som fristående bilagor. Av huvudbetänkandet framgår hur bilagornas analyser och slutsatser använts i utredningens arbete.

Denna bilaga har utarbetats av Teodora Borota Milicevic, universitetslektor vid Uppsala universitet. De åsikter om uttrycks i denna bilaga är författarens egna.

Arbetet med bilagan har följts av en referensgrupp bestående av Lars Calmfors, Peter Englund (t.o.m. april 2023), Urban Hansson Brusewitz, Johannes Lindvall, Johan Lyhagen, Marcus Mossfeldt, Hovick Shahnazarian och Karl Walentin.

Thomas Eisensee, Harry Flam, Nils Gottfries, Anna Seim, Lars E.O. Svensson och Hanna Ågren har gett värdefulla bidrag som kommentatorer.

Ett särskilt tack riktas till

Bilagans författare vill tacka Nils Gottfries för värdefulla synpunkter.

Stockholm december 2023

| Marcus Mossfeldt | Hovick Shahnazarian |

Projektledare, Långtidsutredningen

Table of Contents

5

| Table of Contents | SOU Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

4.2.1Lasting scarring effects and benefits of the big

| crises......................................................................... | 65 |

4.3Greening of the economy – important factors in future

6

Summary

The last four decades have seen weaker economic performance in many advanced economies, with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates following a downward path since the late 1990s. The growth rates have reached levels up to 1.5 percentage points lower than in the 1980s. In Sweden, on the other hand, the growth rate was strong in the late 1990s and early 2000s but has also deteriorated and returned to slightly lower levels compared to the early 1980s. Economic analysis of this

This report explores the potential GDP's mediumand

7

| Summary | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

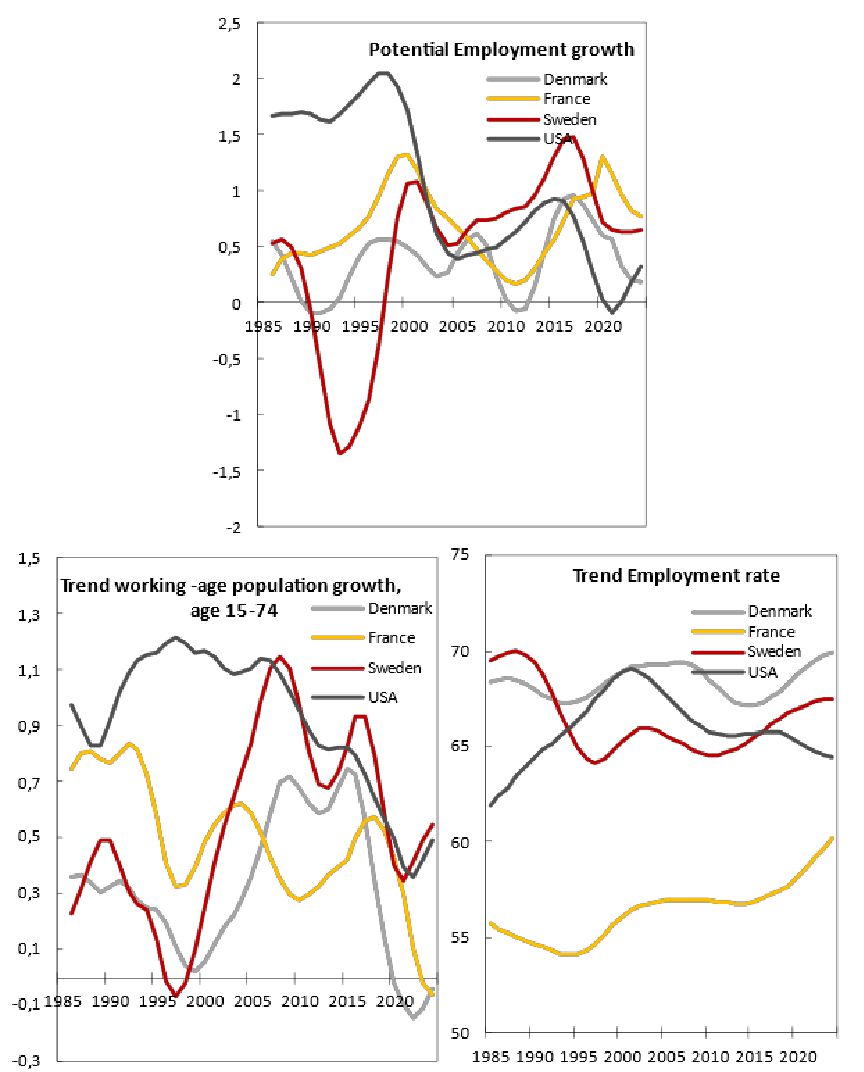

In many advanced economies, the trend in the prospective

The primary factor influencing

8

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Summary |

Total factor productivity (TFP), as the ratio of an economy's output to its total inputs, has been the key contributor to labor productivity and total output growth since World War II. The decline in TFP growth, on average, has been widespread across the developed world. Some research suggests that the decline is due to diminishing productivity benefits of new technologies, while others suggest failures of innovation policies and weak investment. Swedish experience resembled those of the US and UK, with the strongest growth occurring in the ICT sector. The financial crisis and Great Recession had further negative implications on TFP growth, with a strong initial contraction but also the recovery after 2010.

Looking ahead, forecasting potential output and growth in the near and long run is challenging due to the prolonged economic implications of the

9

| Summary | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

potential positive developments. Labor productivity growth is projected to rise from less than 1 to 1.5 percent by 2030 and remain stable throughout the period. TFP growth, labeled as the sole source of potential output growth in the EU Commission forecasts, will be recovering but only up to

Finally, a crucial policy issue - climate change mitigation and greening of the economy – is in the focus of many debates. To achieve net carbon neutrality by 2050, world economies must implement large and rapid policy interventions, including greenhouse gas (GHG) emission taxes, emission trading systems, government regulation of emissions, and investment in

10

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Summary |

about negative pressures on potential GDP growth due to the reallocation of investments to climate adaptation purposes.

11

Sammanfattning

Under de senaste fyra decennierna har många avancerade ekonomier haft svaga ekonomiska resultat, där bruttonationalproduktens (BNP) tillväxttakt följer en nedåtgående trend sedan slutet av 1990- talet. Tillväxttakten har legat på nivåer upp till 1,5 procentenheter lägre än på

I denna bilaga undersöks den potentiella utvecklingen av BNP på medellång och lång sikt för Sverige och andra jämförbara länder. Trenden i potentiell produktion analyseras genom dess två huvudkomponenter, trenden i arbetade timmar och arbetsproduktivitet,

13

| Sammanfattning | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

där den senare drivs av förändringarna i kapital per enhet arbete, humankapital och total faktor produktivitet (TFP).

I många avancerade ekonomier har trenden i den framtida arbetsåldern

Den primära faktorn som påverkar det långsiktiga ekonomiska välbefinnandet är arbetsproduktiviteten, vilken har förmågan att kompensera för negativa förändringar i andra strukturella faktorer. En betydande nedgång i dess tillväxt under de senaste decennierna har varit den mest anmärkningsvärda faktorn bakom den ekonomiska utvecklingen. Med undantag för korta intervaller med högre resultat, som i USA och Sverige i slutet av

– kapital per enhet arbete och total faktorproduktivitet (TFP) – sticker ut. I Sverige började nedgången i kapitalbildning och fördjupning (tillväxt i kapitalbeståndet per enhet arbete) på

14

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Sammanfattning |

många avancerade ekonomier har ackumuleringen av immateriellt kapital accelererat och överstigit materiella investeringar. Sverige har sedan mitten av

Total faktorproduktivitet (TFP), förhållandet mellan ekonomins produktion och dess totala insatser, har varit den viktigaste bidragande faktorn till arbetsproduktivitet och total produktionstillväxt sedan andra världskriget.

Framtida prognoser om potentiell produktion och tillväxt på kort och lång sikt är utmanande på grund av de långvariga ekonomiska konsekvenserna av

15

| Sammanfattning | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

nomier, om än något senare och på något högre nivåer. En positiv effekt som

Slutligen är en avgörande politisk fråga – begränsning av klimatförändringarna och greening of the economy - i fokus för många debatter. För att uppnå netto koldioxidneutralitet till 2050 måste världsekonomierna genomföra stora och snabba politiska åtgärder, inklusive växthusgasutsläppsskatter, system för handel med utsläpp, regeringsreglering av utsläpp och investeringar i koldioxidsnåla tekniker. IMF World Outlook 2020 rapporterar måttliga kostnader för optimala policypaket, som förväntas ha en nettopositiv effekt på den globala

16

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Sammanfattning |

förhindras samtidigt som

17

1 Introduction

Potential output or potential gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of the production capacity of an economy, a level of output that the economy can sustain given its available resources, implemented technology and the full efficiency at which those can be combined. As such, it is one of the central concerns of economic policy. Over a longer term, potential GDP, particularly in its per capita level, presents the main measure of (material) welfare level of a society, correlating positively to almost all measures of its living standards. Furthermore, potential GDP is the main reference for assessing the trend

This report discusses the

Section 2 presents the actual GDP developments since the 1980s in several advanced economies and in Sweden, analyses the main contributing factors of growth, focusing on the GDP growth slowdown observed across the economies. Understanding GDP growth as a

19

| Introduction | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

from the actual unemployment. Section 3.3.1 presents the definition and development of potential hours worked in the selected advanced economies. Moving forward, Section 4 presents the forecasts on future potential GDP and its growth, relying on the OECD, The EU Commission and the NIER analyses. Section 5 provides a final discussion on the key findings of the report and points to several important factors and policy challenges for the future. In particular, climate policy issues, globalization trends and the potential output measurement challenges are addressed.

20

2Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s

2.1GDP growth slowdown

Following the

These developments have long been in the focus of the economic analysis, searching for the sources of the weaker growth performance among the structural components of GDP, permanent and

1The selected group of analyzed countries include advanced EU economies, France and Germany, Denmark as a Scandinavian economy, UK and the USA.

2Growth slowdown is even more significant if the latest decade’s observed rates are compared to the decades prior to 80’s which points to a

21

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980sBilaga 1 till LU2023

| Figure 2.1 | Trend GDP growth since 1980 (in percentage), selected | |

| countries | ||

| 4 | ||

| 3,5 | Denmark | Germany |

| 3 | France | Sweden |

| 2,5 | UK | USA |

2

1,5

1

0,5

0

| 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2024 |

Note: The presented trend is calculated by applying the Hodrick

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112) and own calculations.

2.2Reasons for the decline

Relying on the definition of the trend output growth as a purely

22

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

Sections

Figure 2.2 Illustration of GDP Components

| Technology | |||||||||

| Total Factor | |||||||||

| Productivity | |||||||||

| Efficiency | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| Human capital | |||||||||

| Labor | |||||||||

| productivity | Training and | ||||||||

| experience | |||||||||

| Capital (physical | New capital | ||||||||

| acummulation | |||||||||

| and knowledge- | |||||||||

| GDP | based) per unit of | ||||||||

| Depreciation | |||||||||

| labor | |||||||||

Employment

population

Hours worked

worked

2.2.1Hours worked

Recent demographic developments with a marked slowdown in population growth (and population ageing affecting the share of dependent population and GDP per capita) have had a significant draw on the hours worked growth in many advanced countries (e.g. US and France) These changes have been compensated to a larger or smaller degree by stronger participation in the labor force and higher employment rates across countries. In some other economies, such as Sweden and Denmark, the negative demographic changes have not been experienced, partly due to strong fertility and immigration. Overall, with a notable exception of the US, the growth in hours worked have been relatively stable, or even remarkably stronger as in Sweden, in the analyzed period (see Figure 2.3), which shifts the

23

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

focus on labor productivity as the potential source of the observed GDP developments.

Figure 2.3 Trend growth in total hours worked (in percentage)

2

1,5

1

0,5

0

| 1981 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

DenmarkGermany

| France | Sweden | |||

UKUSA

Note: The presented trend is calculated by applying the Hodrick

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112) and own calculations.

2.2.2Labor productivity

GDP per hour worked is the main driver of the long run development in economic welfare of population, with the capacity to compensate for the negative developments of other structural factors that lie largely outside the scope of economic policy, such as demographics. The most striking feature of economic developments in the past four decades (and longer) has been a significant downturn in the trend labor productivity growth. As shown in Figure 2.4, this slump has been experienced across all advanced economies, only with the exception of limited periods of stronger performance such as those in the US and Sweden in the end of ‘90s and beginning of 2000s. In this period, the Swedish economy caught up with the US, overpassing other advanced European economies, and in the two subsequent decades the developments in Swedish growth mimic the general trends. There is still an ongoing discussion in the economic

24

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

literature and debates on the potential reasons for the “productivity slump”, among other the nature and implementation process of the new (ICT) technologies. Up until the Great Recession, the trend in productivity was expected to recover as the new digital economy finally transformed the ways businesses operate and use their inputs. This development was awaited as productivity growth is typically expected to play the largest role in output growth over the projections and beyond.3

Figure 2.4 Trend growth in labor productivity (in percentage)

4

DenmarkGermany

3,5

| France | Sweden | |

| 3 | UK | USA |

2,5

2

1,5

1

0,5

0

| 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

Note: The presented trend is calculated by applying the Hodrick

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112) and own calculations.

As the most important driver of the developments in the trend GDP level and growth rate, labor productivity is also the biggest contributor to the actual GDP level and growth as well as to their developments over time. (see Figure 2.5).

3There is, however, an ongoing debate about exactly how much one can expect productivity growth to rise (Schembri 2018).

25

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

Figure 2.5 Decomposition of GDP growth rate in Sweden, hours worked growth and labor productivity growth (in percentage)

| 8 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Total hours worked | Labor Productivity | GDP Growth | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1985 1987 1989 1991 | 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 | 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 | 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112).

Human Capital

Labor input, measured by the employment and average hours worked, accounts only for the volume of this factor of production. The quality of labor factor, labeled as human capital, includes labor knowledge, skills and its ability, affecting the efficiency of physical (and other forms of) capital utilization, and is thus partly determining the productivity growth. The evolution of labor input quality and changes in labor composition have historically been some of the key growth promoting factors, alongside the TFP growth.

As it is embodied in the labor itself, human capital is very hard to measure. It is typically determined by the level of education and training and experience workers obtain during their working life, on average. In practice, most often it is represented simply by the average years of schooling or completion rates by education level. Educational attainment measured by the average years of schooling has been on a steady rise since 1980 in most of the world economies, including Sweden (see Figure 2.6). Right panel reveals the sources of the average years of schooling increase in Sweden. While the initial

26

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

improvements occurred due to a rise in both the shares of population with secondary and tertiary education until early 2000s, the subsequent developments have been entirely driven by the rise in the highest education group shares, once the only primary education group share has reached low levels.4 This points to the fact that the Swedish education attainment is well in a phase where college education becomes the norm for the labor market.

Figure 2.6 Education as a measure of human capital: average years of schooling (left panel) and the population shares by education level in Sweden (right panel)

| 14 | 80 | |

| 13 | % of population in Sweden | ||||||||||||||

| 70 | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | |||||||||||||||

| 60 | |||||||||||||||

| 11 | Primary | ||||||||||||||

| 10 | 50 | Secondary | |||||||||||||

| 9 | Denmark | 40 | Tertiary | ||||||||||||

| Germany | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | France | ||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 30 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | UK | ||||||||||||||

| USA | |||||||||||||||

| 20 | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 |

Source:

It should be noted that the human capital level is not a uniform measure across the labor force as represented by the average years of schooling. Workers differ in their education level, quality of education, skills and abilities, and thus their contribution to productivity, which may also be changing over time5. Differences in productivity contributions are normally captured in wages which are in turn used for the calculation of weighted or quality adjusted labor

4Nevertheless, a persistent problem in the labor market is a high level of unemployment among the

5For example, fast technological progress introducing new ways of working may renders certain forms of education and training obsolete over time. Age, on the other hand, affects human capital through the tradeoffs between a higher work experience (older workers) and a more recent,

27

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

services6, but a special attention should be given to potential discriminatory wage penalties, which among other issues render the wage a poor proxy of productivity. (NIER 2008) Finally, common measures of human capital do not fully capture the value of productive services of this type of capital. Labor skills and abilities are only contributing to output if they are properly matched with the productive requirements of the jobs where labor is employed, an aspect which becomes increasingly important in the times of rapid technological and structural changes. Persistent misalignment between the demand and supply of skill at the aggregate and micro level leads to lower labor productivity reflected in workers compensations. OECD (2016b) review on the Swedish labor force skills development and allocation reveals that while 33 percent of firms report difficulties in hiring due to a lack of appropriate skills, around 34 percent of workers experience field of study mismatch, 39 percent are mismatched by qualifications (either higher or lower) and around 11 percent are mismatched by skills.

Physical and

Growth in capital intensity, i.e. the capital per unit of labor input (per hour worked, or per worker), is another factor of crucial contribution to the labor productivity growth. Total capital stock grows due to continuous investments, corrected for the depreciation and scrapping of the obsolete capital. In its intensive form, it measures how

6The OECD Measuring Productivity Manual (OECD, 2001) lays out an approach to account for the heterogenous human capital where workers are grouped by their marginal productivities proxied by different characteristics (age, education, occupation, sex). Each group’s contribution to economic growth is then calculated through the contribution of the growth rate in the group’s hours worked weighted by its share in total income accruing to the labor factor. Using this approach, a study based on labor data from a subset of the OECD economies finds that the labor quality composition accounted for 20 percent of labor productivity growth in the

28

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

growth and capital accumulation. A lower growth in labor force implies a lower need for investment in order to keep the

However, capital deepening has showed similar negative developments over the last four decades, with a higher or lower trend over periods depending on the labor input growth. On average, capital deepening rates have ended up at levels

7Arguably, these links between capital accumulation and population and employment trends have greatly affected the prevailing real interest rates in the global economy.

8A decade after the wake of the financial crisis of 2007, OECD countries on average experienced a 0.4 percentage point drop in the annual capital deepening rate and can account for the slowdown in trend productivity growth in the

29

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980sBilaga 1 till LU2023

| Figure 2.7 | Capital deepening (trend), total for selected countries and by | ||

| capital type in Sweden | |||

| 6 | 25 | ||

| Denmark | |||

| Germany | Sweden | ||

| 5 | |||

| France | 20 | Total | |

| Sweden | capital | ||

| UK | ICT | ||

| 4 | USA | capital | |

| 15 | |||

| capital | |||

| 3 | |||

| 10 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 1 | 5 | ||

| 0 | 0 | ||

| 1985 1989 1993 1997 2001 2005 2009 2013 2017 2021 | 1985 1989 1993 1997 2001 2005 2009 2013 2017 2021 | ||

Note: The presented trend is calculated by applying the

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112) and own calculations.

Disaggregating the total capital into Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) capital and

A bulk of studies that aim to quantify the importance of different contributors to output growth has failed to account properly for the category of

9

30

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

There are many forms of capital used in the production processes. The most traditional notion of physical capital in its intensive form, indicates how much of the physical capital (machines, equipment, buildings, infrastructure) is used by a worker, and it is a product of the installed capital capacity and the measure of the intensity of its usage. This traditional view differs from the way we think about the new forms of capital in modern economies. The new form of

aproduct of firms’ investment in

KBC is intangible in its nature and, historically, the national accounts analysis and empirical studies have had difficulties in measuring KBC and accounting for several of its forms, e.g. firmspecific training, design, innovative property and organizational quality. Recent two decades have seen substantial advances on this front, most notably the introduction of the expenditure-

10Corrado et al. (2009) find that the intangible investment in the U.S. started to grow faster than tangible investment in the 1970s and accounting for these trends, the contribution of TFP growth to labor productivity growth has been revised downwards, from 35 percent to

25percent in the

31

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

based treatment of KBC (an investment instead of intermediate consumption) which has spurred growth accounting studies estimating the KBC investment contribution to economic growth, but there are still outstanding issues particularly regarding consistency and comparability across countries. An important conclusion is that different kinds of capital have different productivities. In order to properly account for those in a growth accounting exercise, one is advised to consider different forms of capital separately.11

Figure 2.8 presents the contribution of different categories of capital deepening to labor productivity growth. Sweden has proved to be among the countries with substantial contribution of intangible and

11Analysts typically distinguish between several different forms of capital: tangible

32

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

Figure 2.8 Contribution of different types of capital deepening to Labor productivity growth: intangible vs. tangible assets

| 1,8 | ||||||||||||||

| Labor composition | Tangible |

1,6 | ||||||||||||

| Tangible ICT | Intangible | 1,4 | ||||||||||||

| TFP | Labor Productivity | |||||||||||||

| 1,2 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 0,8 | ||||||||||||||

| 0,6 | ||||||||||||||

| 0,4 | ||||||||||||||

| 0,2 | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||||||||

| France | United Kingdom | Denmark | Germany | United States | Sweden | |||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Tangible |

||||||||||||||

| 2,5 | ||||||||||||||

| Tangible ICT | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Intangible | ||||||||||||||

| 1,5 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 0,5 | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||||||||

Source: EUKlems & INTANProd Database, 2023.

Total Factor Productivity (TFP)

Total factor productivity (TFP) is the ratio of the measure of output in an economy and the measure of total inputs used (labor and

33

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

different types of capital), combined according to the production function. TFP growth is thus a difference between the growth rate of total output and the weighted growth rates of inputs. In other words, growth in TFP measures all the changes in output that cannot be attributed directly to the changes in the quantity of labor and capital inputs generating that output. Therefore, assessing the contribution of the total factor productivity (TFP) trend growth depends crucially on the ability to properly quantify the contributions of other factors, as the TFP growth is in turn treated as the residual development. Using modern techniques and considering all the possible types of assets with increasingly important shares in the economy, the TFP growth contribution still stays firmly in the first place of important contributors to labor productivity and total output growth. Trends in the TFP have indeed been driving labor productivity in the advanced economies since the World War II. This empirical finding goes in line with the predictions with almost all of the existing growth models.12

Components and drivers of TFP growth

The main component of the TFP growth is technological change (see e.g. Basu and Fernald (2002) for evidence). This is not to say that TFP growth does not change for reasons different than improvements in technology; institutional change, market deregulation and removal of distortionary tax systems can serve as examples of efficiency changes affecting trend TFP growth. However, many of the central efficiency improvement policies and regulations have already been implemented in the advanced economies which probably leaves the technological progress as the main contributor to TFP growth. Some growth studies add the “scale change” component to the classification of TFP growth components – a factor conditional on recognizing potential deviations from constant returns to scale technology which allows for productivity benefits that rise or fall with the scale of production.

A notable efficiency channel affecting TFP growth operates through reallocation of resources within and across firms and

12For a comprehensive review on the traditional and modern growth theory, see Appendix A.

34

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

industries, driven by exposure to competition in domestic and foreign markets. The Swedish economy, as a small open economy with a large share of firms involved in international trade and competition in global markets, has experienced significant changes and potentially large associated efficiency benefits from globalization. (Jakobsson 2007)

The OECD report “The Future of Productivity” (OECD, 2015) offers a structured analysis of the TFP growth drivers and identifies the three main categories:

•Factors that incentivize innovation – research and development (R&D), digitalization and investment in intangible capital;

•Factors driving knowledge and technologies diffusion – labor skills and qualifications, and public infrastructure; and

•Factors and institutions that ensure efficient allocation of resources within and/or between sectors and firms: competition and business dynamics, globalization and financial development.

Regarding the first group of factors, one should note that a large body of empirical literature points to a positive causal link between research and development (R&D) and TFP growth, stemming from both the private (within firm) and public R&D investment, domestic and foreign.13 Since 2008, the System of National Accounts treats the R&D expenditure (a part of the

13Recent empirical studies and literature surveys include, among others, Wieser (2005), Coe et al. (2009), Hall (2011), Ang and Madsen (2013) and Herzer (2022).

35

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

knowledge transfers occur through FDI, trade in intermediate and final goods and services as well as through the movement of (skilled) labor, materializing the benefits of globalization. Higher level of human capital, investment in tangible ICT capital and better quality of institutions, among other factors, show strong complementarities with R&D in its effect on TFP growth. (Guellec and Van Pottelsberghe, 2004)

The decline in trend TFP growth is not an entirely uniform phenomenon across countries14, but on average, the slump has been widespread across the developed world (see Figure 2.9). Some research has taken a stand that the TFP growth slump is a result of a diminishing ability of newer technologies to provide substantial productivity benefits (Gordon 2012), while others discuss failures of different government policies promoting innovation and, more recently, the linkages between weak investment and productivity growth that may have applied in the aftermath of the financial crisis. (Arsov and Watson 2019). Recent evidence in Gordon and Sayed (2019) in fact reveals a remarkably similar development in the U.S. and the

14For example, while some European economies experienced a persistent or

36

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s |

Figure 2.9 Trend TFP growth in selected countries (in percentage)

| 2,5 | ||

| Denmark | Germany | |

| 2 | ||

| France | Sweden | |

| 1,5 | UK | USA |

| 1 |

0,5

0

Note: The presented trend is calculated by applying the Hodrick

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112) and own calculations.

After a weaker performance in the ‘80s, the development of trend TFP growth in Sweden resembled the US and the UK experience, as opposed to the developments in some other advanced European economies such as France and Germany. The second half of the ‘90s decade and early 2000s was marked by a strong TFP growth (well above 1 percent in trend TFP growth in the

The implications of the financial crisis and the Great Recession for the TFP level and growth were large.15 TFP is by itself procyclical and was driven down by the large contractions in the economies during the crises, but has remained low even in the years after the crises, raising the issue of potential

15For more details on the developments and mechanisms during the Great Recession

37

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth since the 1980s | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

the recovery after 2010 (Tillväxtanalys 2021). Given that the TFP growth is estimated as the residual after other factors’ growth contribution to labor productivity growth have been accounted for, these findings should be assessed together with the developments in, first of all, capital deepening which has been somewhat less volatile compared to many other advanced economies.16

16Large falls in TFP growth do not necessarily reflect a reduction in the pace of technological innovation, but may come as a result of smaller contractions in capital deepening in times of large potential output growth drops. Thus, they should rather be understood as falls in efficiency growth. i.e. factors other than technology.

38

3Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

To analyze the structural component of GDP, historically and forecasting into the future, economists employ the notion of potential output – the sustainable level of output capturing the key aspects of

Figure 3.1 Output concepts – Potential, actual and trend GDP (LHS) in billions constant SEK; GDP gap (RHS) in percentages (Sweden)

| 7 000 000 | ||

| GDP Gap | Potential GDP | 23,5 |

| 6 000 000 | ||

| GDP | GDP trend | 18,5 |

| 5 000 000 | ||

| 13,5 | ||

| 4 000 000 | ||

| 3 000 000 | 8,5 | |

| 2 000 000 | 3,5 | |

| 1 000 000 | ||

| 0 |

1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021 2023

Note: The presented GDP trend is calculated by applying the

Source: NIER and own calculations.

39

Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s Bilaga 1 till LU2023

Over longer time horizons, as shown in Figure 3.1, one can project a fairly smooth growth path in the actual output data - the GDP trend (grey line). The trend itself is a measure fairly close to the notion of potential output (blue line), but which may diverge to a larger or smaller extent from it over periods.

Over the shorter horizons,

With the focus on the

3.1Definition of potential GDP

The potential output (GDP) in the long run17 is defined as the level of sustainable real output in the economy when all available productive

Potential GDP is to a large extent an abstract theoretical concept and is mostly shaped by structural forces characterized by a slow evolution of demographic trends, capital accumulation and technological progress. However, there is no reason to regard the potential output as a perfectly smooth path.

17At this instance,

40

Bilaga 1 till LU2023 Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

deep and permanent policy changes, especially in the domain of fiscal policy, can change the course of the potential output. Policies that promote incentives for the development of technology, infrastructure, labor supply and human capital can have substantial implications for potential output.

Economic theory recognizes also the temporary

Shifting the focus to

41

Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s Bilaga 1 till LU2023

implications for the assessment of the current state of the economy, i.e. the output gap, and the stabilization policy.18

To a large extent, the choice of the time horizon and the precise concept and measurement method applied in the potential output analysis depends on the policy area of interest. The structural longterm analysis is concerned with the optimization of

Therefore, possible distinction between the potential output and growth concepts over the short and

Estimation methods used by main international institutions and in Sweden

Many international organizations and institutions provide estimates of potential output and its growth for advanced economies, most notably the Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Commission (EC), joined by the National agencies such as national economic research institutes and Central Banks. The estimation methods

18Recent

42

Bilaga 1 till LU2023 Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

are very similar, mostly relying on growth accounting approach and expert judgement.

In Sweden, The National Institute of Economic Research (NIER) focuses on estimating the components of potential output when the economy is in the cyclical balance, i.e. when the resources are used normally. For unemployment, a reference period is chosen to represent the cyclical balance in the labor market and different models are used to assess how structural factors, including demographic changes, have affected equilibrium unemployment19 relative to the reference period. The size and composition of the potential labor force is determined through projections of the cyclically adjusted series using the demographic development, while potential average working time is obtained through

The Government of Sweden also relies on similar methods, production function approach and growth accounting, with the analysis and estimation of the equilibrium unemployment rate in focus20. (The Government Office 2022)

19In calculating potential labor input, i.e. hours worked, NIER relies on the concept of equilibrium unemployment instead of NAIRU

20The Government uses the

43

Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s Bilaga 1 till LU2023

3.2The development of potential GDP and components

The hypothetical nature of potential output makes it hard to measure and predict its values in the future when an economic analyst has only the real

Other more sophisticated international estimates of potential growth over the last four decades also reveal a steady decline since the

21The Euro area as a whole has as well experienced the lower reduction in potential growth trend, mostly due to milder developments in the demographic trends, although both the potential growth and the population growth are lower compared to other major advanced economies.

44

Bilaga 1 till LU2023 Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

Figure 3.2 Potential growth in selected advanced economies,

Note: Data for years 2023 and 2024 present the OECD forecast.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112).

3.3The development of factors driving the potential

GDP

Similarly to the discussion in Section 2.2, one can analyze the trend in potential output through the lenses of its two main components, trend in hours worked and labor productivity, respectively, where each can be further decomposed into the contributing factors. By the methodology used by the main institutions providing the estimates of potential output, all the components of potential labor productivity (except capital stock) are the trend components obtained by applying the HP filter on the actual data series, where the OECD also conducts cyclical adjustment of the series prior to filtering. Capital stock is assumed to contribute to potential output in its full and thus remains unadjusted. For those reasons, the analysis of the potential labor productivity is practically the same as the one presented in Section 2.2 where the trend components of actual GDP can be interpreted also as their potential counterparts. Where most divergence between the measures of potential output

45

Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s Bilaga 1 till LU2023

and the actual series trend may occur is in the potential hours worked component which depends on the estimates of the equilibrium unemployment. The definition and the evolution of potential hour worked in the selected advanced economies is presented in Section 3.3.1

3.3.1Potential hours worked

Trend potential growth in hours worked is a measure of potential labor supply growth in the economy. It is determined by the following factors:

•Trend in the

•Trend employment rate, and

•Trend in average hours worked conditional on employment/working

The first two factors determine the potential employment of an economy in terms of the number of people working. The trend in working age population is driven by demographic forces, while the trend employment rate, as the employed workers share in the

Notable demographic changes in the advanced economies in recent decades – slower population growth and population ageing – have been reducing the trend in the potential

22Many institutions reporting the measures of potential variables rely on a

46

Bilaga 1 till LU2023 Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

in total and per capita, respectively, as they falter the labor supply growth and the

Equilibrium employment rates in the economies facing negative developments in the

23With a notable exception of Finland which has experienced increases in employment rate.

47

Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s Bilaga 1 till LU2023

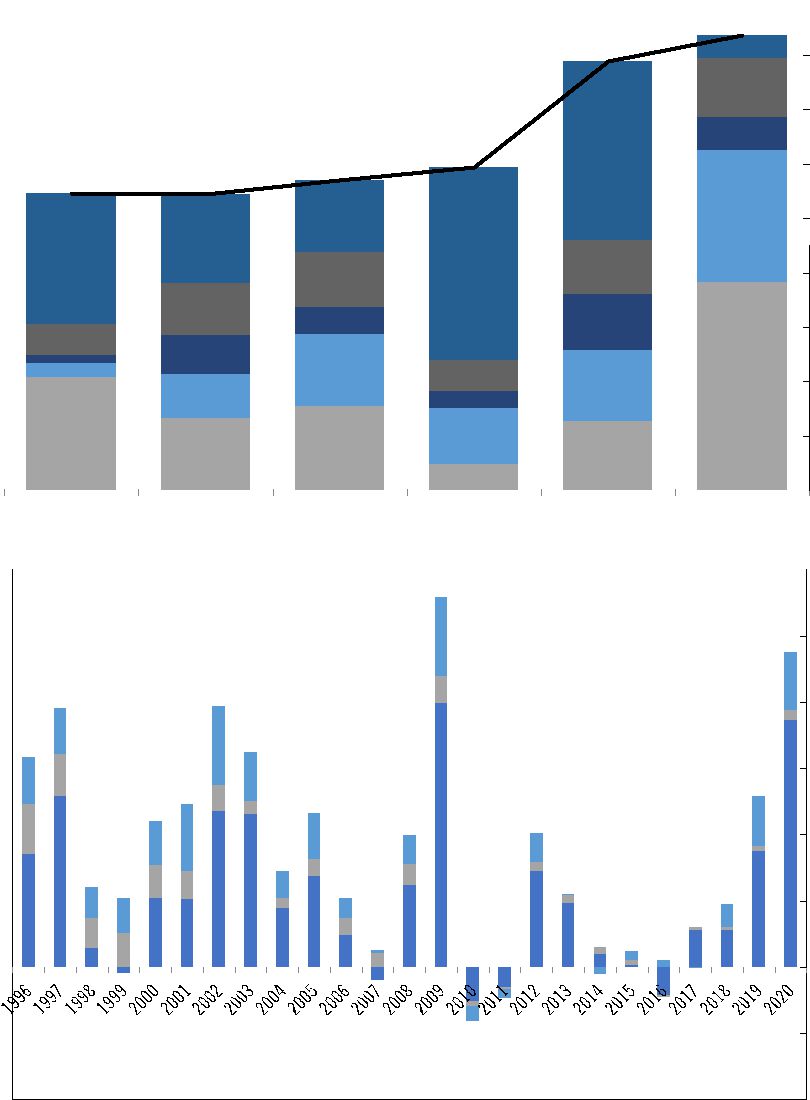

Figure 3.3 Potential Employment development, with contributing components

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112).

Two factors stand behind the potential employment rate developments – the labor force participation rate and the equilibrium unemployment rate as shown in Figure 3.4. Participation rates have varied over the observed period, with somewhat stronger positive trends up to the Great Recession

48

Bilaga 1 till LU2023 Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

positive contributors to the participation rate have been found in a finer disaggregation by gender and age.

Figure 3.4 Employment rate factors

| 80,00 | Trend Participation rate | ||||||

| 75,00 | |||||||

| 70,00 | |||||||

| 65,00 | |||||||

| 60,00 | |||||||

| Denmark | |||||||

| 55,00 | France | ||||||

| Sweden | |||||||

| USA | |||||||

| 50,00 | |||||||

| 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

85Trend Participation rate, female

| 80 | |||||||

| 75 | |||||||

| 70 | |||||||

| 65 | |||||||

| 60 | Denmark | ||||||

| France | |||||||

| 55 | Sweden | ||||||

| 50 | USA | ||||||

| 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

| 10,00 | Equilibrium Unemployment rate | ||||||

| 9,00 | |||||||

| 8,00 | |||||||

| 7,00 | |||||||

| 6,00 | |||||||

| 5,00 | |||||||

| 4,00 | |||||||

| 3,00 | Denmark | ||||||

| France | |||||||

| 2,00 | Sweden | ||||||

| USA | |||||||

| 1,00 | Sweden_NIER | ||||||

| 0,00 | |||||||

| 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

20Trend Participation rate, 65+

| 18 | |||||||

| 16 | |||||||

| 14 | Denmark | ||||||

| 12 | France | ||||||

| 10 | Sweden | ||||||

| USA | |||||||

| 8 | |||||||

| 6 | |||||||

| 4 | |||||||

| 2 | |||||||

| 0 | |||||||

| 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

Note: The presented participation rates trends are calculated by applying the

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112), NIER and own calculations.

An increase in the female participation (that varied in magnitude and timing across the economies), and a notable increase in the older workers (65 years or older) participation rates, especially after 2000s have come as a continuing response to structural and policy changes as well as population ageing, respectively. However, although

49

Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s Bilaga 1 till LU2023

increasing the participation, females and old workers tend to work fewer hours which has muted the effect on potential hours worked growth24. The population is projected to age further which will expectedly bring further changes in the rates across the age segments of the

Observed stagnation or decrease in the rate of equilibrium unemployment in Figure 3.425 has contributed positively to the developments of the potential employment rates as more people in the labor force are able to find jobs. In Sweden, the equilibrium unemployment rate experienced a large increase in the early ‘90s due to a series of adverse macroeconomic shocks, and has since fallen but remains high relative to the

Finally, potential total hours worked trend draws significantly on the developments in the trend hours worked per worker, besides the trend in potential employment (Figure 3.5). Hours worked per worker have been on decline, markedly affected by the increase in the share of

24In countries with the most notable increase in the share of these groups in the labor force, average hours worked per employed have declined.

25The Figure presents the OECD data which uses the trend NAIRU equilibrium unemployment concept until 2021. For Sweden, as reported by the NIER, a

50

Bilaga 1 till LU2023 Potential GDP – definition(s), measurement and development since the 1980s

| Figure 3.5 | Trend Average Hours Worked | ||||||||||||||

| 1900 | Trend Hours worked per worker | 1000 | Trend Hours worked per capita | ||||||||||||

| 1800 | 900 | ||||||||||||||

| Denmark | |||||||||||||||

| 1700 | France | 800 | |||||||||||||

| Sweden | |||||||||||||||

| USA | |||||||||||||||

| 1600 | 700 | ||||||||||||||

| 1500 | 600 | ||||||||||||||

| Denmark | |||||||||||||||

| 1400 | 500 | France | |||||||||||||

| Sweden | |||||||||||||||

| USA | |||||||||||||||

| 1300 | 400 | ||||||||||||||

| 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

Note: The presented trend is calculated by applying the Hodrick

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (112), SCB and NIER, and own calculations.

Overall, the common feature of the advanced economies has been a decline or stagnation in the potential employment growth which has then failed to contribute to the potential output growth.

In Sweden, however, there has not been such an obvious negative overall development, Potential labor force growth has stabilized at around 1 percent, mainly due to the strong and rising participation rate in prolonged periods, and a stronger increase in the trend

51

4 Forecasts

4.1Potential growth and its deriving forces in future

According to the OECD forecasts in 2020 (Figure 4.1), the global potential output growth is projected to slow further in most advanced economies up to 2060, with a relative stagnation in European economies that have previously experienced lower rates.

| Figure 4.1 | OECD Potential Growth Forecast, 2060 | |

| 10Y annual rate average, forecast from 2020; annual growth | ||

| 4,5 | ||

| 4 | Denmark | |

| France | ||

| 3,5 | Germany | |

| Sweden | ||

| 3 | United Kingdom | |

| United States | ||

| Euro area (17 countries) | ||

| 2,5 | OECD - Total | |

| 2 | ||

| 1,5 | ||

| 1 | ||

| 0,5 |

0

| 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 |

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (108), long

The forecast is relatively uniform across countries with all presented economies potential growth converging to

26In a global perspective, from a historical 3.6 percent in global potential output growth in the decade before the Great Recession, global economy is projected to slow down to 2.8 percent growth in the

53

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

Demographic trends are determined to be the key factor responsible for this growth tendency.

The EU Commission forecasts on the EU countries is somewhat more optimistic (Figure 4.2). Growth on average is projected to reach 1.2 percent up to 2030, increase slightly in 2030s and 2040s, and afterwards stabilize.

Figure 4.2 EU Commission Potential growth forecast, 2060

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

0,5

0,0

DenmarkGermany

FranceSweden

EU

| 2019 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2055 | 2060 |

Source: EU Commission, DG ECFIN 2021 Ageing Report.

The EU Commission projections as well stress out the demographic trends as the main growth reducing component, which again puts forward the future labor productivity growth as the main driver of positive developments. The forecasts on these components of potential output growth in future are presented in the sections below.

4.1.1Labor supply growth in future

Demographic trends are expected to be the most important component of the growth decline globally until 2060. After having contracted from 2 to 1 percent over the past six decades, global population growth is projected to nearly halt by 2060. Although a

54

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

slower growing population relaxes some of the (resource) sustainability threats, it lowers the growth in labor input. OECD forecast (Figure 4.3) predict a stable decline in potential employment growth up to 2060 due to a strong contraction in

Figure 4.3 OECD Population growth and

| 1,2 | 2,0 | |||||||||||

| OECD Total | Denmark | |||||||||||

| Potential Employment growth | ||||||||||||

| 1,0 | France | |||||||||||

| Germany | ||||||||||||

| 1,5 | ||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||

| Sweden | ||||||||||||

| 0,8 | ||||||||||||

| UK | ||||||||||||

| 0,6 | 1,0 | USA | ||||||||||

| Euro area (17 | ||||||||||||

| countries) | ||||||||||||

| 0,4 | 0,5 | OECD - Total | ||||||||||

| 0,2 | ||||||||||||

| 0,0 | ||||||||||||

| 0,0 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 | |||||

| 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 | ||||||

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (108), long

Projections of the EU Commission are very similar (Figure 4.4). Potential labor input growth will make a negative contribution to potential output growth

27When translating the demographic changes into their effects on potential output growth, many forecasters often assume constant participation (and structural unemployment) rates which implies that a reduction in

55

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

coupled with a decline in the average hours worked. Again, Sweden is expected to share the general potential employment trend of the other advanced economies, although at a lag and at higher levels.

Figure 4.4 EU Commission forecast on labor input components growth, 2060

| 1,5 | 1,5 | |

| Employment |

Hours worked growth | |

| Denmark | ||

| 1,0 | Germany | 1,0 |

| France | ||

| Sweden | ||

| 0,5 | EU | 0,5 |

| 0,0 | 2019 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 | 0,0 |

| 2019 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 | ||

Source: EU Commission, DG ECFIN 2021 Ageing Report.

The phenomenon of slower population growth is coupled with population ageing which increases dependency ratios and causes economic challenges for the development of potential growth per capita. Moreover, the sustainability of health and pension systems are at risk, as the share of

56

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

Figure 4.5 Economic

Inactive population 65+ / employment

80,0

| 70,0 | ||||||||

| 60,0 | ||||||||

| 50,0 | ||||||||

| 40,0 | ||||||||

| 30,0 | Denmark | Germany | ||||||

| France | Sweden | |||||||

| 20,0 | EU | |||||||

| 10,0 | ||||||||

| 0,0 | ||||||||

| 2019 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2055 | 2060 |

Source: EU Commission, DG ECFIN 2021 Ageing Report.

In the EU population, the share of people of 65 years of age or more was 20.8 percent in 2021, while this number is expected to rise to 30 percent by 2050, increasing the dependency ratio to close to 70 percent (less than two

1.9percentage points from initial 24 percent in 2019, with the health care costs being the biggest contributor to the increase. At the same time, the young population is shrinking, failing to fully replace the

57

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

4.1.2Labor productivity growth in future

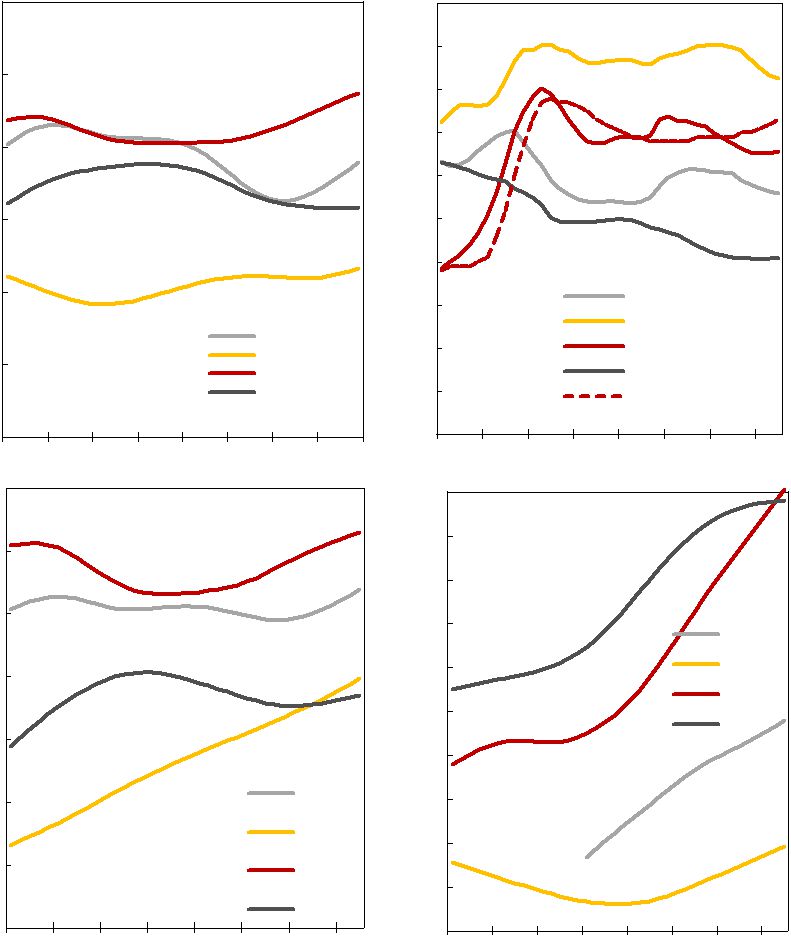

OECD (2015) notes that with the slowdown in population growth (and rise in population aging which is relevant for potential growth in per capita terms) and the limitations in human capital development which is hindered by decreasing marginal returns to education at its higher levels, the weight of TFP growth in driving future growth prospects will be rising (see Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6 OECD Trend growth in TFP forecast, 2060

| 3,5 | ||||||

| 3 | Denmark | |||||

| Germany | ||||||

| 2,5 | Sweden | |||||

| United States | ||||||

| 2 | Euro area (17 countries) | |||||

| OECD - Total | ||||||

| 1,5 | ||||||

| 1 | ||||||

| 0,5 | ||||||

| 0 | ||||||

| 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 |

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database (108), long

Trend TFP growth is expected to rise in most presented countries up to rates of 1.5 percent by the 2040s and afterwards stabilize, except in the US where the developments are negative (shrinking to 1.2 percent).

EU Commissions predictions are somewhat more pessimistic. TFP growth as the sole source of potential output growth is expected to recover but only up to

58

Bilaga 1 till LU2023Forecasts

| Figure 4.7 | EU Commission forecasts on labor productivity growth (left) and | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TFP growth (right), 2060 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2,0 | 1,4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,8 | Labor Productivity growth | TFP growth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,4 | 1,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,2 | Denmark | 0,8 | Denmark | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| France | France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,8 | Sweden | Sweden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EU | EU | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,6 | 0,4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,2 | 0,2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,0 | 0,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | 2055 | 2060 | 2019 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | 2060 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Source: EU Commission, DG ECFIN 2021 Ageing Report

At the same time, there are large uncertainties on how the future TFP growth will develop and potential failures of predictions and their implications are analyzed in the assessment of risk scenarios. Learning from the recent history, the ICT sector and the investments in tangible and particularly

59

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

up and the revival of economic growth. Countries that host a significant share of successful global companies and

Concerning the very new technologies and their development and transmission, economists and the industry typically agree that the benefits of the second stage of the digital revolution (driven by the AI technologies) will be realized. Labeling these advances as a General Purpose Technology (GPT) economic models and historical experience tell us that the GPTs, not only require the necessary complementary resources and conditions, but also wide adoption with a significant lag. In his New York Times Opinion post Krugman (2023) debates on the two key questions: how large the productivity effects will be, and how quickly they will come about. While the first question hardly can be answered by any expert or policy maker, the answer to the second question relies greatly on our experience from the past which suggests very long lags before the AI benefits finally materialize. At least longer than what most people currently expect. Nevertheless, adoption lags are greatly affected by the policy.

4.2Potential growth developments in future Sweden

This section discusses the NIER (2022) forecasts on the future of Swedish potential output in the next decade (up until 2032) from the perspective of the main driving factors, and also those that are specific for the Swedish economy.

Predictions on the potential growth slowdown are similar to the EU commission projections. Regarding the relation of potential growth to the actual GDP growth in the near future, the Swedish economy is predicted to overcome the current negative output gap by 2026 (Figure 4.8).

60

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

Figure 4.8 Swedish Potential GDP growth and the

3,0

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

0,5

0,0

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 |

Potential GDP growth

Source: NIER 2023.

In the developments thereafter, the most important contributor to output growth in the following

In the public finance sustainability analyses by NIER made for this report, the forecast extends to 2100. Labor productivity is predicted to grow at 1.3 percent per year, and until 2050 GDP growth forecast is just above 1.5 percent per year after an initial cyclical adjustment.

61

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

Figure 4.9 Swedish GDP growth projections with contributing factors growth, 2032

| 3,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | ||||||||||||||||

| GDP | Hours worked | Labor productivity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: NIER 2023.

Potential labor input growth

The labor input growth predictions are in line with the forecasts of international institutions in terms of the downward trend and the resulting potential employment and hours worked growth rates in 2032 (0,4 percent). A fall in the potential labor force growth (stemming from

62

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

Figure 4.10 Potential hours worked growth with components (equilibrium unemployment right axis), 2023

| 1,2 | 7,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,0 | 7,4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,2 | Potential hours worked growth | Potential employment growth | 7,2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential labor force growth | Equilibrium unemployment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,0 | 7,1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | |||||||||||||||||

Source: NIER 2023.

It is argued that structural transformation in the economy brings increases in the separation rates of

63

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

Potential labor productivity growth

Figure 4.11 Potential productivity growth and the productivity gap, 2023

| 2,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0,0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | ||||||||||||||

| Potential productivity growth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Productivity gap, % of potential labor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| productivity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: NIER 2023.

Potential productivity growth is expected to rise from 1 percent to 1,2 percent by 2025 and then experience another rise by 0,1 percentage point by 2029 where it will stabilize. The negative productivity gap is projected to turn slightly positive in 2026 and diminish thereafter (Figure 4.11). Several important factors for the productivity development are put forward.

Technological change is virtually impossible to predict, but judging by the innovation climate and incentives, the NIER predicts a rise in its pace in the near future. Furthermore, technical transformation towards production that uses sustainable energy sources may be

64

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

consequences for the growth rate as the sectors experience very different rates of productivity growth. Public (excluding health) and health sectors both have lower productivity growth rates compared to the business (private) sector. The public sector is projected to experience very weak productivity growth rates in the next decade, while the health sector is expected to increase its share in the total economy as the population ages, each in turn contributing to the aggregate economy reducing its productivity growth further relative to the business sector.

4.2.1Lasting scarring effects and benefits of the big crises

Large economic, natural and

Most advanced economies have rebounded their productivity growth rates to a larger or lesser degree during the decade following the financial crisis and the resulting Great Recession

On the other hand,

65

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

Possible

Two main consequences of the Great Recession are discussed in the literature. First, longer spells of unemployment have had negative consequences on

Another caveat relates to the uncertainty on the magnitude and implication of the “cleansing effect” of the Great Recession. Recessions drive unproductive firms out of business and reallocate resources towards more productive firms and their more efficient use, ultimately raising aggregate productivity. The question surrounding the Great Recession is whether its cleansing effect has been too harsh. Some evidence on the U.S. economy shows that the recessionary effects were similar as in previous episodes but less

The economic research and literature on the

66

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

As with the Great recession, the “cleansing effect” operating at the

On the positive note, the pandemic has incentivized the adoption of digital technologies and teleworking. Although it is very hard to establish a causal relationship between digitalization and productivity growth (as more productive firms can also be expected to have higher incentives and capacity to invest in digitalization), but at the aggregate level, acknowledging the reallocational effects, recent trends on productivity of the digitally intensive sectors point to further productivity benefits due to their higher ability to adapt to the new conditions. Teleworking, on the other hand, involves several effects that are perhaps easier to identify but include both positive and negative factors so that the overall assessment is hard to establish. The future forecasts on the summarized relationship between teleworking and workers efficiency may well prove to be of an inverted

4.3Greening of the economy – important factors in future potential growth

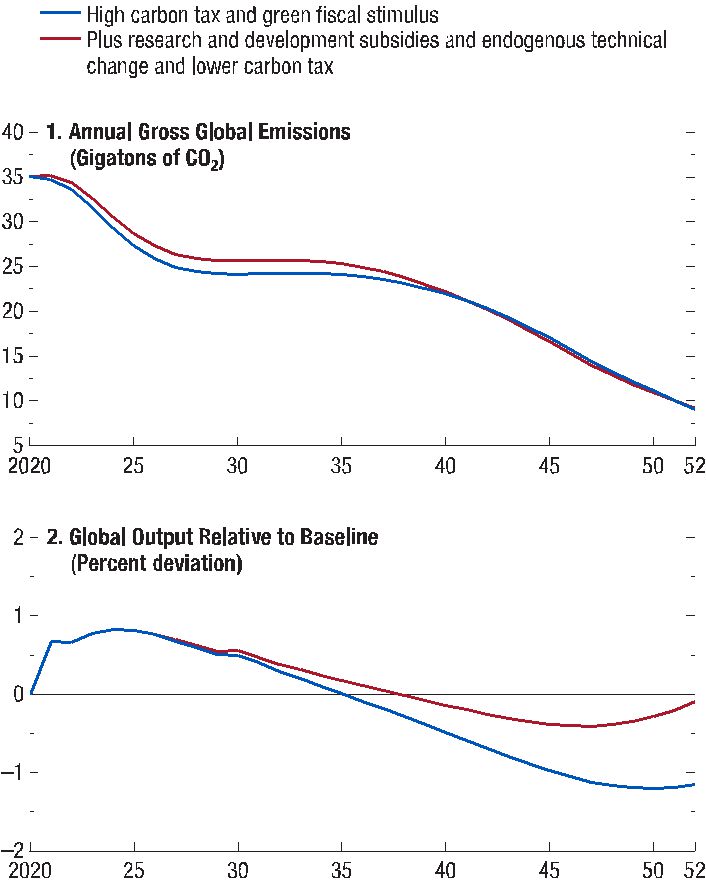

In order to reach the goal of net carbon neutrality by 2050 (2015 Paris Agreement), world economies need to conduct large and rapid policy interventions. By 2030, global emissions need to be reduced by at least 25 percent compared to today’s levels which among other things requires greenhouse gas (GHG) emission taxes, emission trading systems, government regulation of emissions and investment in

67

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

policy makers around the world have been significant, against the widely accepted agreement that consequences of inaction may be catastrophic and that the

The IMF World Outlook 2020 reports the results of the analysis of the effects of climate mitigation policy on climate problems and the economic outcomes of the global economy. Optimal policy package (in terms of reaching the agreed limits for emission and global temperature rise) costs are moderate while they are expected to have net positive effect on global growth in the initial years, supporting the recovery from

68

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

Figure 4.12 Mediumto

Percent of baseline GDP

Note: The figure shows the variation over output gains from climate change mitigation due to

uncertainty from two sources: local costs of higher temperatures, from either Nordhaus (2010) or Burke, Hsiand, and Miguel (2015); and climate sensitivity, measured as the increase in long

Source: IMF staff estimates, IMF World Outlook 2020 .

Important aspect of climate mitigation policy and investment is its ability to generate significant returns to the support of technological innovation, largely absent from the models used to conduct policy scenario evaluations. Carbon taxes and green R&D subsidies both affect technological innovation and produce long run growth benefits. It is estimated that the resulting technical change stemming from changes in carbon prices and a complementary 70 percent subsidy would reduce the needed carbon prices for achieving the emissions targets by half, compared to the scenario without the technical change channel. At the same time, focusing on the period until 2050, the actual GDP would be starting to approach the baseline earlier, around

28The figure is comparing the scenario accounting for the technical change, (lower) carbon tax, fiscal stimulus and R&D subsidies to the scenario with only carbon tax and fiscal stimulus

(though it’s a high carbon tax here). Thus, carbon tax is included in both, just showing that it

69

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

stemming from the nature of technological innovation and diffusion is the fact that the positive effects come only after a certain lag, i.e. after 2030, relative to a scenario without R&D subsidy and endogenous technical change.

Finally, another aspect of green technologies spillovers should be noted. New energy sources and decarbonizing technologies may provide significant productivity benefits, but it may as well be the case that the climate transition will bring about negative pressures on potential GDP growth due to a reallocation of investments to climate adaptation purposes. These investments may raise the

may be lower if we allow for the assumption on positive technological change. It may be argued that the market allocation should be more efficient, but we should also account for this important growth driving channel.

70

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Forecasts |

Figure 4.13 The role of Green Technological Change

Note: The panels compare the

Source: IMF staff estimates, IMF World Outlook 2020.

The recent IMF World Outlook 2023 report points to several challenges in the climate change mitigation policy. The global financial crisis and the war in Ukraine that have led to a retreat from

71

| Forecasts | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

mitigation. While there are encouraging signs of international cooperation on adaptation to climate change, more needs to be done, including channeling aid to vulnerable countries. Furthermore, the International Energy Agency predicts an 80 percent reduction in global fossil fuel extraction by 2050, requiring a significant reduction in production. This could have economic repercussions for fossil fuel exporters, as the industry negatively impacts a country's economic growth and institutions, as well as on their trading partners. A new data set on oil, coal, gas, and metal extraction from 1950 to 2020 identifies that a typical episode of contraction is a 10 percent contraction in extraction activity in the episode's first year that cumulates to a 40 percent reduction over 10 years. The macroeconomic effects of these declines are negative, with a typical episode leading to a 1 percent initial decline in real GDP, a 5 percent decline after five years, and a slow depreciation of the real exchange rate. The impact on manufacturing and services sectors is significant and negative, with a negative impact on employment. The estimated GDP impact is larger for middleand

72

5 Discussion

5.1What do the forecasts show? Discussion

The forecasting work is an interplay between models and assessments. To varying degrees, models assume that history repeats itself or that economic relationships are stable over time, and therefore they also need to be supplemented by analyses and judgements by experts who have an insight into mechanisms and economic developments that the models do not always capture. The overall information from the models is finally weighed together with other information to produce forecasts for economic activity and inflation. The experts’ assessments become particularly important when unusual events and/or structural changes that alter the functioning of the economy take place. (Riksbanken, 2022)

Forecasting potential output and its growth in the near future and in the long run implies facing difficult tasks. Producing some medium run projections involve the assessment of the prolonged economic implications of the

Predicted demographic changes are difficult to discuss from the stand point of an economic policy makers. These developments are driven by the deep structural processes and the variables such as fertility rates are difficult to tackle with a single or a small set of policies. Favorable developments require a whole environment of

73

| Discussion | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

good economic and social conditions over a prolonged period. This is not to say that policy cannot affect potential labor input growth. Indeed, the forecasts show that economies that manage to sustain labor force inflow that matches the skill requirements of jobs across industries and that have

At the global level, views on the future of TFP growth have become polarized. The

In the aspects currently considered to be the most relevant for the TFP growth (as discussed in previous sections), Sweden is well equipped to expect stable if not positive developments in TFP growth. Both

74

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Discussion |

most sectors and firms, with large firms, employing the major share of the labor force, being more

Globalization has proved to incentivize labor reallocation across industries and firms, promoting better

5.2Important remaining factors

World economy is a highly integrated network of regions, markets, and global production chains. The use of digital technologies is erasing the borders even further. Virtually every economic decision has to be based on the information about conditions in various segments of those networks, and every action has implications for other parties involved. From this perspective, two policy aspects which will certainly have implications for the development of potential output in the near and far future should be mentioned as some final remarks.

Climate change as an international challenge

Judging from the experience of many countries, Goldman Sachs (2022) argues that there is no necessary strong negative correlation between potential economic growth and environmental

75

| Discussion | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

sustainability, and the policies designed to tackle each of the issues can be

However, the climate change issues cannot be addressed independently from other countries. Sweden is at the forefront in terms of the implemented policies but the effectiveness of these policies in fighting the climate problems will depend on the policy responses of other economies. This in turn may require recalibration of the national policies and a possibly larger negative effects on potential GDP growth, at least in the

Globalization – reversal (deglobalization), slowdown (slowbalizations) or the rise of new forms?

Globalization has proved to be a powerful force in shaping living standards and income distribution across the world over the major part of our economic history, only to be interrupted by large recession episodes often accompanied by a rise in protectionist policies. Having experienced two of the largest crises in just 15 years, an unprecedented disruption in globalization momentum has followed. As globalization and technological progress are highly interlinked processes, this creates increased risks for the evolution of TFP. Moreover, continuing efficiency gains in the future will largely depend on the countries’ tendency to revert to protectionism. Goldman Sachs (2022) predicts a slowdown in the following decade(s), with the risk of deglobalization always present. Swedish economic agents have understood the benefits of globalization for a small open economy early, but the future benefits in Sweden are crucially dependent on the decisions and policies of other players in the global markets. A hardly predictable mix of political, technological and economic factors and shocks that is driving technological development in a globalized world is largely out of the reach of national policies, but is an important factor to take into account when producing potential productivity and growth forecasts.

76

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | Discussion |

5.3Scope for methodological improvement

Currently used potential GDP measurement methods by NIER, among others, largely disregard the lower frequency supply shocks when estimating potential productivity. The intention is to capture only the long run, structural

Furthermore, as noted by the OECD regarding their measurement, the coefficients relating external measure of cyclical indicators to labor efficiency or participation needs constant updating for the proper estimation of the potential GDP components.

On the other hand, as the OECD points out in the description of its method (Chalaux and Guillemette, 2019),

Finally, inclusion of the natural resource capital for greater degree of freedom in making forecasts on the climate change policy effects, as well as different measurement techniques for the aspects related to the Digital economy and the rise in consumer welfare, are just some of the possible venues for methodological improvement.

77

References

Acemoglu, Daron (2007). Introduction to Modern Economic Growth. USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Aghion, Philippe, David Hemous, and Enisse Kharroubi. (2014). Cyclical fiscal policy, credit constraints, and industry

growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 62, pp.

Ang, James.B. and Jakob B. Madsen (2013). International R&D Spillovers and Productivity Trends in the Asian Miracle Economies. Economic Inquiry, 51(2), pp.

Araujo, Carlos Hamilton (2009), The Role of Potential Output Growth in Monetary Policymaking in Brazil. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 91(4), pp.

Arsov, Ivailo and Benjamin Watson (2019). Potential Growth in Advanced Economies. Reserve Bank of Australia, Bulletin- December 2019, Global Economy.

Barro, Robert J. (2006). Rare disasters and asset markets in the twentieth century. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121 (3), pp.

Barro, Robert J. and

Basu, Susanto and John G. Fernald (2009). What Do We Know (And Not Know) About Potential Output?. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 91(4), pp. 187

Baziki, Selva B., Borota Milicevic, Teodora and Rita Ginja (2016). Trade Competition, Technology and Labor

79

| References | Bilaga 1 till LU2023 |

Bernanke, Ben S. (1983).

Blagrave, Patrick, Mr Roberto

Bloom, Nicholas, Sadun, Raffaella and John Van Reenen (2012). Americans do I.T. better: US multinationals and the productivity miracle. NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper 13085.

Bontadini, Filippo, Carol Corrado, Jonathan Haskel, Massimiliano Iommi, and Cecilia

Boianovsky, Mauro and Kevin D. Hoover (2009) The Neoclassical Growth Model and 20th Century Economics. History of Political Economy, 41,

Bresnahan, Timothy.F., Brynjolfsson, Erik and Lorin M. Hitt. (2002). Information Technology, Workplace Organisation and the Demand for Skilled Labor:

Burke, Marshall, Hsiang, Solomon M. and Edward Miguel (2015). Global

Cahn, Christophe and Arthur

Chalaux, T. and Y. Guillemette (2019). The OECD potential output estimation methodology. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1563, OECD Publishing, Paris,

Coe, David T., Helpman, Elhanan, and Alexander W. Hoffmaister (2009). International R&D spillovers and institutions. European Economic Review 53(7), pp.

80

| Bilaga 1 till LU2023 | References |

Coibion, Olivier, Gorodnichenko, Yuriy and Mauricio Ulate, M (2018). The Cyclical Sensitivity in Estimates of Potential Output. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2018(2), pp

Corrado, Carol, Charles Hulten, and Daniel Sichel. (2009). Intangible capital and US economic growth. Review of income and wealth, 55(3),

Corrado, Carol, Haskel, Jonathan, Iommi, Massimiliano and Cecilia

Cotis,

Davidson, Carl, Heyman, Fredrik, Matusz, Steven, , Fredrik and Susan Chun Zhu (2012). Liberalized Trade and

Dieppe, Alistair and M.Ayhan Kose (2020). The Global Productivity Slump: What policies to rekindle. The Brookings Institution, November 2020.